This little Babe, so few days old,

Is come to rifle Satan's fold.

All Hell doth at His presence quake,

Though He Himself for cold do shake.

For in this weak, unarmed wise,

The gates of Hell He will surprise.

With tears He fights and wins the field;

His naked breast stands for a shield.

His batt'ring shot are babish cries,

His arrows looks of weeping eyes,

His martial ensigns Cold and Need,

And feeble flesh His warrior steed.

His camp is pitched in a stall,

His bulwark but a broken wall;

A crib His trench, haystalks His stakes;

Of shepherds He His muster makes.

And thus-- as sure His foe to wound--

The angels' trumps alarum sound!

My soul, with Christ join thou in fight,

Stick to the tents that He hath pight.

Within His crib is surest ward;

This little Babe will be thy guard.

If thou wilt foil thy foes with joy,

Then flit not from this heavenly Boy!

-Robert Southwell

Though each day may be dull or stormy, works of art are islands of joy. Nature and poetry evoke "Sehnsucht," that longing for Heaven C.S. Lewis described. Here we spend a few minutes enjoying those islands, those moments in the sun.

28 December 2006

12 December 2006

Giving thanks for art

I came across another great G.K. Chesterton quote lately:

You say grace before meals.

All right.

But I say grace before the play and the opera,

And grace before the concert and the pantomime,

And grace before I open a book,

And grace before sketching, painting,

Swimming, fencing, boxing, walking, playing, dancing;

And grace before I dip the pen in the ink.

Cited in Frederick Buechner's Speak What We Feel (Not What We Ought To Say), which in turn was cited by Ron Reed in his blog Oblations.

You say grace before meals.

All right.

But I say grace before the play and the opera,

And grace before the concert and the pantomime,

And grace before I open a book,

And grace before sketching, painting,

Swimming, fencing, boxing, walking, playing, dancing;

And grace before I dip the pen in the ink.

Cited in Frederick Buechner's Speak What We Feel (Not What We Ought To Say), which in turn was cited by Ron Reed in his blog Oblations.

11 December 2006

How to read the Narnia Chronicles

Several of my students (and their parents) have recently been asking me "What's the right order in which to read the Narnia Chronicles?" Actually, they probably said "What's the right order to read Narnia in" since they're in my Inklings class and not my grammar-crazy writing class, but that's OK. The purpose of language is the communication of ideas, and I understood them. Well, there are lots of other purposes of language, too, including patterns & the sheer beauty of the sounds & traditions & wrestling with the ineffable, etc. So.

But back to Narnia. Well, I told them that I didn't think it mattered in which order they read the Narnia Chronicles. I added that I had a slight preference for the "Published" order, but that's only because that's how I was raised, and I'll never forget the moments of wonder & revelation when I read The Magician's Nephew for the first time. Wow. But I didn't know which order Jack himself preferred.

So first of all, which order do you prefer? And why?

And then here's a really good posting on that over at another web site called What Order Should I Read the Narnia Books in (And Does It Matter?). I couldn't discover the author. Please do read it, and please read all of it, if you can. There are some very interesting points, especially the quote from Lewis. And I wonder what you think of the ending of this article?

By the way, I was really glad that the new movies are being made in the "original" order (even though that idea is now skewed a bit by that article), but I think we should all write to Douglas Gresham & beg him on bended knees to make sure the screenplay of Prince Caspian is much, MUCH more accurate than LWW! Sure, Disney probably thinks that modern viewers are too dumb for that kind of slightly elevated British 1950s English. But, as CSL himself said in the preface to Mere Christianity, "I don't think the average reader [viewer] is such a fool." Hear, hear.

But back to Narnia. Well, I told them that I didn't think it mattered in which order they read the Narnia Chronicles. I added that I had a slight preference for the "Published" order, but that's only because that's how I was raised, and I'll never forget the moments of wonder & revelation when I read The Magician's Nephew for the first time. Wow. But I didn't know which order Jack himself preferred.

So first of all, which order do you prefer? And why?

And then here's a really good posting on that over at another web site called What Order Should I Read the Narnia Books in (And Does It Matter?). I couldn't discover the author. Please do read it, and please read all of it, if you can. There are some very interesting points, especially the quote from Lewis. And I wonder what you think of the ending of this article?

By the way, I was really glad that the new movies are being made in the "original" order (even though that idea is now skewed a bit by that article), but I think we should all write to Douglas Gresham & beg him on bended knees to make sure the screenplay of Prince Caspian is much, MUCH more accurate than LWW! Sure, Disney probably thinks that modern viewers are too dumb for that kind of slightly elevated British 1950s English. But, as CSL himself said in the preface to Mere Christianity, "I don't think the average reader [viewer] is such a fool." Hear, hear.

06 December 2006

The Myth of Talent?

Paul Butzi has a couple of good posts on the myth of talent over at his blog, Musings on Photography: the first is here with follow-ups here and here. I've commented on the first of those on his blog. His thesis is essentially that innate talent is an overrated notion. There is no way of gauging a person's early talent that will predict whether he will end up successful as an artist. It is only in hindsight that you can recognize talent. Furthermore, this mysterious thing called talent is no substitute for hard work. Given enough determination and practice, even someone who did not think she was talented can develop the skill to make good art. Deciding after a couple of false starts that you have no talent and just giving up on art would be a tragedy, whether you're destined to become another Rembrandt or not. Here's my friend Jayne's great story of how she never thought she'd become a good knitter but then persistence paid off. Her present passion for knitting (addiction, one might call it) means she gets tons of practice and gets better and better. You should see some of the amazing stuff she does (all photographed and shown off on her blog, See Jayne Knit).

Of course as a Christian I believe that there are gifts bestowed by God, including artistic gifts. Some people have them and others don't, or rather some people have certain gifts and other people have other gifts. But I agree with Paul's observations that thinking one has no artistic gifting (or "talent") is no excuse for not working hard to develop it (and even, I might add, to discover it in the first place). Even the most gifted artists have to work at their art. A lot of times an artistic talent can be buried by hurtful (and untrue) comments made to one during childhood by insensitive adults. While it is not always the case, usually you will find in the background of great artists a supportive parent or patron. Mozart, for example, doubtless had a larger measure of gifting/potential in the area of music than most of us do, but he was also fortunate enough to have had a supportive father who took him all over the place to play for and get training from famous musicians. Some artists who have suffered early discouraging remarks have been able to break through that later in life and rediscover and develop their creative gifts. The Artist's Way: A Spiritual Path to Higher Creativity by Julia Cameron helps people do that.

Of course as a Christian I believe that there are gifts bestowed by God, including artistic gifts. Some people have them and others don't, or rather some people have certain gifts and other people have other gifts. But I agree with Paul's observations that thinking one has no artistic gifting (or "talent") is no excuse for not working hard to develop it (and even, I might add, to discover it in the first place). Even the most gifted artists have to work at their art. A lot of times an artistic talent can be buried by hurtful (and untrue) comments made to one during childhood by insensitive adults. While it is not always the case, usually you will find in the background of great artists a supportive parent or patron. Mozart, for example, doubtless had a larger measure of gifting/potential in the area of music than most of us do, but he was also fortunate enough to have had a supportive father who took him all over the place to play for and get training from famous musicians. Some artists who have suffered early discouraging remarks have been able to break through that later in life and rediscover and develop their creative gifts. The Artist's Way: A Spiritual Path to Higher Creativity by Julia Cameron helps people do that.

01 December 2006

December Poem of the Month

It certainly is not feeling like Christmas around here; 70 degrees today.... But here's a Christmas poem to help usher in Advent. It's a few years old now, and stylistically outdated, but perhaps you'll find something to enjoy notwithstanding.

Incarnation

Immense and joyful was His infinite

existence, massive both in size and bliss,

in cosmic comfort, starry celebration,

and sustained aseity of happiness.

He folded up that hugeness slowly. In

an instant crammed into the virgin’s seed,

gently holding back so not to burst

by size and speed: and thus contained knew grief.

When born, He suddenly was jarred by pain,

embraced by arms that, too, knew pain, and lost

the warm protection of that prenatal place.

Stabbed with sudden hurts, He later stood

on weak legs, scarce contained by skin, and lost

the cool perfection of an infinite space.

~ Sørina

© 2002, Sørina Higgins. Do not use this work in any way without permission from the author.

Incarnation

Immense and joyful was His infinite

existence, massive both in size and bliss,

in cosmic comfort, starry celebration,

and sustained aseity of happiness.

He folded up that hugeness slowly. In

an instant crammed into the virgin’s seed,

gently holding back so not to burst

by size and speed: and thus contained knew grief.

When born, He suddenly was jarred by pain,

embraced by arms that, too, knew pain, and lost

the warm protection of that prenatal place.

Stabbed with sudden hurts, He later stood

on weak legs, scarce contained by skin, and lost

the cool perfection of an infinite space.

~ Sørina

© 2002, Sørina Higgins. Do not use this work in any way without permission from the author.

28 November 2006

To photograph, or to take photos?

Interesting post over at Shards of Photography. I quote it in its entirety:

"To photograph" is to talk, to sympathise, to open up to people, to interact and to share your emotions with you[r] subject, and hopefully vice versa. The actual act of tripping the shutter is only second to that. This is in contrast to "to take photos", where a photo is "taken" without "giving". When photographing, the subject gives a part of himself to you in response to your giving your attention, your showing interest, your sympathy. It's still not an equal deal as you gain income, fame or whatever you think to gain from your photographs. The subject most likely doesn't benefit materially from this deal unless he (or often she) is a model posing for you. Often the subject, however, is left with a positive feeling, a sense of importance or just had a pleasant interlude in an otherwise boring day.I think this is very important, as a Christian and a photographer. Creating art with my camera, when it involves a human subject, must involve my relationship with the person I am photographing. I am guilty of "taking photos" when I've shot pictures of charming looking natives in foreign countries where I'm traveling, all from the safe distance of several yards, with a telephoto lens so the subject doesn't even know she's having her image "taken." I am realizing now that, aside from being somewhat unethical (you are supposed to get a person's written permission before publishing a photograph of him anywhere [though I've never published any of these surreptitiously "taken" photos], and in certain cultures having your photograph "taken" is akin to have your soul captured), it is not a very Christian way to do photography. As someone who has been touched by relationship with the Almighty God, I should be ever more keen to engage relationally with the world and the people I photograph. This post by ShardsOfPhotography has really got me thinking.

25 November 2006

Shutter & Palette

This past week G. & I spent our Thanksgiving Vacation in Washington, D. C. In addition to running around looking at the monuments at night (in the freezing cold), touring the Capitol, sitting in the empty House gallery listening to a police officer give his rather leftist interpretation of the intricate workings of the U.S. government, and going hungry because of the atrocious cost of food in our capitol city, we whiled away several afternoons in the excellent Smithsonian museums. I’d like to take a moment to talk about the photography was saw in two to them, and to contrast these to some of the paintings we saw.

Well, first of all I’m wondering what makes a good photograph. Yes, of course, I know this is one of those unanswerable questions, like What is art and Why is this awful piece of music so famous and My 6-yr-old could paint like that what makes it worth hanging in a museum. Right. But I was a little baffled by some of the sharp contrasts we encountered. I’d like everyone to answer, of course, but I’d also like to direct you to Rosie’s photo blog for you to view some contemporary photography & maybe bring it into this discussion.

First of all, we saw a collection of photographs of NYC at the National Gallery of Art. Here are highlights. I was confused by this exhibition. I couldn’t understand why these were worthy to hang in the first art museum in the US of A, why they were supposed to be good. I mean, I’m no photographer, and I know that photographers love to mess with traditional settings, etc., but these were just out of focus, poorly arranged or not intentionally arranged at all (like aleatoric music, perhaps), oddly cropped, and so on. I felt like any hack with a camera could do better. Yet here they were, hung all neatly in their lovely rows, with plaques pronouncing how revolutionary and profound and gritty and full of the sense of life they were. Well, fine, but I didn’t get it.

Then we went on down the road to the Museum of Natural History (or, as we young-earth Intelligent Design Creationist like to call it, the Museum of Unnatural Fiction). There we were swept breathlessly away by a fantastic, gorgeous, stunning display of photographs from the current exhibition of winners from a nature photography contest. Wow! These were just wonderful. Picture after picture, crystal clear, vivid color, astonishing poses, stories printed on the sides of courageous photographers risking their lives to get the perfect picture. Take a look at this one of a giraffe at sunset, or this one of a polar bear afloat on ice. These struck me like the great sky-scapes of Tuner. Then there were astonishing compositions, like this one of an alligator’s snout above & below water. There was one of clownfish, not presented on the website, in which the camera was placed below bright orange seaweed where brilliant orange-and-black clownfish played, and the leaves of a mangrove tree were clearly visible above the water in the sky beyond! Wow. And eagles in their nests, and snow monkeys frolicking in the snow, and owls & bears & flowers. G. asked why these shouldn’t be hung up the street in the National Gallery of Art. And I had to ask the same question. What made these beautiful, carefully crafted pieces “Nature Photography” and what made those fuzzy, haphazard NYC photos art?

Well, of course, it doesn’t really matter. We had our various enjoyments in each building. And people who would be, perhaps, scared away or bored by “Fine Art” were thrilled and blessed by those photos of Creation. So that’s fine.

And then here’s another contrast we experienced. There was one particular image of a bald eagle which became the icon for the entire exhibition. When we viewed it, 5’ long & 3’ high, in stunning color, G. said it looked like a painting. We were shocked that something in nature could be that vivid, that bold, that perfectly posed. The head looked carven, as if out of wood, and painting with sharp contrast. So that was our highest compliment to these photographs: that they resembled paintings. Well, the evening before at the National Portrait Gallery, we had done just the opposite! There was a starting painting of Toni Morrison by Deborah Feingold. When we walked into the spare, primary-yellow room, her figure clad in black & grey, with a determined expression on her face, leapt out at us from the bright white canvas. Unfortunately, this image is not available online. You’ll just have to go to D. C. to see it for yourself! But we could not tell if it was a photograph or a painting. We stood looking at it & guessed before we looked at the caption. One of us thought it was a photo; one, a painting. It was a painting, but you’d be startled to know that. She was coming right off the canvas at us! Her shoulders were a good five inches away from the white background, her hands and elbows and breasts curved outward towards us; and all this in two-dimensions. It amazed me. Here’s the link to the web site of an acquaintance of mine, friend-of-a-friend, who does photorealist paintings. Again, they amaze me.

Of course, you see where I’m going with this. We gave our highest praise to the eagle photo by saying it looked like a painting; we gave our highest praise to the Toni Morrison painting by saying it looked like a photograph. Why is this? Is the goal of visual art, then, to fool its viewers into thinking it’s something it’s not? Or, to put it in different terms, is mimesis primarily a deceptive practice?

And then what about art, specifically photography, that does the opposite: that achieves its artistry by giving an image of something that could occur nowhere outside its borders? I’m talking about “avant-garde,” or specifically “surreal” works, those fantastical images of random (or not-so-random) juxtaposition like this one of paper clips and cows by Rosie.

I have not even begun to talk about the ideological or spiritual implications of these questions. It seems obvious to me that an artists could incorporate surreal elements as religious statements that there’s-more-than-meets-the-eye, or that some people could take offense at what they see as the deceit of some art, or that comments could be made on social interrelationships by visual juxtapositions, or that photography & painting can slide in and out of one another as multiple visions of the way things are & they way they should be & the way the artists sees them & the way they could be.

Feel free to speculate.

Well, first of all I’m wondering what makes a good photograph. Yes, of course, I know this is one of those unanswerable questions, like What is art and Why is this awful piece of music so famous and My 6-yr-old could paint like that what makes it worth hanging in a museum. Right. But I was a little baffled by some of the sharp contrasts we encountered. I’d like everyone to answer, of course, but I’d also like to direct you to Rosie’s photo blog for you to view some contemporary photography & maybe bring it into this discussion.

First of all, we saw a collection of photographs of NYC at the National Gallery of Art. Here are highlights. I was confused by this exhibition. I couldn’t understand why these were worthy to hang in the first art museum in the US of A, why they were supposed to be good. I mean, I’m no photographer, and I know that photographers love to mess with traditional settings, etc., but these were just out of focus, poorly arranged or not intentionally arranged at all (like aleatoric music, perhaps), oddly cropped, and so on. I felt like any hack with a camera could do better. Yet here they were, hung all neatly in their lovely rows, with plaques pronouncing how revolutionary and profound and gritty and full of the sense of life they were. Well, fine, but I didn’t get it.

Then we went on down the road to the Museum of Natural History (or, as we young-earth Intelligent Design Creationist like to call it, the Museum of Unnatural Fiction). There we were swept breathlessly away by a fantastic, gorgeous, stunning display of photographs from the current exhibition of winners from a nature photography contest. Wow! These were just wonderful. Picture after picture, crystal clear, vivid color, astonishing poses, stories printed on the sides of courageous photographers risking their lives to get the perfect picture. Take a look at this one of a giraffe at sunset, or this one of a polar bear afloat on ice. These struck me like the great sky-scapes of Tuner. Then there were astonishing compositions, like this one of an alligator’s snout above & below water. There was one of clownfish, not presented on the website, in which the camera was placed below bright orange seaweed where brilliant orange-and-black clownfish played, and the leaves of a mangrove tree were clearly visible above the water in the sky beyond! Wow. And eagles in their nests, and snow monkeys frolicking in the snow, and owls & bears & flowers. G. asked why these shouldn’t be hung up the street in the National Gallery of Art. And I had to ask the same question. What made these beautiful, carefully crafted pieces “Nature Photography” and what made those fuzzy, haphazard NYC photos art?

Well, of course, it doesn’t really matter. We had our various enjoyments in each building. And people who would be, perhaps, scared away or bored by “Fine Art” were thrilled and blessed by those photos of Creation. So that’s fine.

And then here’s another contrast we experienced. There was one particular image of a bald eagle which became the icon for the entire exhibition. When we viewed it, 5’ long & 3’ high, in stunning color, G. said it looked like a painting. We were shocked that something in nature could be that vivid, that bold, that perfectly posed. The head looked carven, as if out of wood, and painting with sharp contrast. So that was our highest compliment to these photographs: that they resembled paintings. Well, the evening before at the National Portrait Gallery, we had done just the opposite! There was a starting painting of Toni Morrison by Deborah Feingold. When we walked into the spare, primary-yellow room, her figure clad in black & grey, with a determined expression on her face, leapt out at us from the bright white canvas. Unfortunately, this image is not available online. You’ll just have to go to D. C. to see it for yourself! But we could not tell if it was a photograph or a painting. We stood looking at it & guessed before we looked at the caption. One of us thought it was a photo; one, a painting. It was a painting, but you’d be startled to know that. She was coming right off the canvas at us! Her shoulders were a good five inches away from the white background, her hands and elbows and breasts curved outward towards us; and all this in two-dimensions. It amazed me. Here’s the link to the web site of an acquaintance of mine, friend-of-a-friend, who does photorealist paintings. Again, they amaze me.

Of course, you see where I’m going with this. We gave our highest praise to the eagle photo by saying it looked like a painting; we gave our highest praise to the Toni Morrison painting by saying it looked like a photograph. Why is this? Is the goal of visual art, then, to fool its viewers into thinking it’s something it’s not? Or, to put it in different terms, is mimesis primarily a deceptive practice?

And then what about art, specifically photography, that does the opposite: that achieves its artistry by giving an image of something that could occur nowhere outside its borders? I’m talking about “avant-garde,” or specifically “surreal” works, those fantastical images of random (or not-so-random) juxtaposition like this one of paper clips and cows by Rosie.

I have not even begun to talk about the ideological or spiritual implications of these questions. It seems obvious to me that an artists could incorporate surreal elements as religious statements that there’s-more-than-meets-the-eye, or that some people could take offense at what they see as the deceit of some art, or that comments could be made on social interrelationships by visual juxtapositions, or that photography & painting can slide in and out of one another as multiple visions of the way things are & they way they should be & the way the artists sees them & the way they could be.

Feel free to speculate.

20 November 2006

Short thoughts on contemporary fantasy

I was just informed by one of my students today that Eragon is "The best book ever." I wonder if any of my readers share that opinion? I haven't read it yet, and will try to do so before The Movie comes out in December. So I'd love to read your thoughts on this book -- no spoilers, please!

And then let's expand the conversation a bit further. You Harry Potter fans: what's so good about it? Does Rowlings stand up to Lewis & Tolkien, think you? Are her books "great literature," whatever that may be, and will they find a place in the Canon, whatever that is & whoever decides what goes in it?

And (thanks for doing my research for me), I'm wondering who the other heirs of The Inklings' imagination might be? I plan to talk about this at the end of my current course on MacDonald, Lewis, Tolkien, & Charles Williams. I'd include Dorothy Sayers, Christopher Tolkien, Owen Barfield, Walter Wangerin, Jr., Madeleine L’Engle, Mervyn Peake, Phillip Pullman.... Who else would you include, and why? I'd love recommendations, reviews of these books/authors/movies, links, and all intelligent thoughts on -- what shall we call it? -- spiritual fantasy?

I'll try to chime in more profoundly at some point.

And then let's expand the conversation a bit further. You Harry Potter fans: what's so good about it? Does Rowlings stand up to Lewis & Tolkien, think you? Are her books "great literature," whatever that may be, and will they find a place in the Canon, whatever that is & whoever decides what goes in it?

And (thanks for doing my research for me), I'm wondering who the other heirs of The Inklings' imagination might be? I plan to talk about this at the end of my current course on MacDonald, Lewis, Tolkien, & Charles Williams. I'd include Dorothy Sayers, Christopher Tolkien, Owen Barfield, Walter Wangerin, Jr., Madeleine L’Engle, Mervyn Peake, Phillip Pullman.... Who else would you include, and why? I'd love recommendations, reviews of these books/authors/movies, links, and all intelligent thoughts on -- what shall we call it? -- spiritual fantasy?

I'll try to chime in more profoundly at some point.

12 November 2006

"Performing" Scripture -- The Lord's Supper

In a comment on an earlier post, I wrote:

As to whether there can be multiple different valid "performances" of Scripture, I think there can. Let me just take the eucharist as one small example to show how. Until I was in my 20's I had rarely experienced a communion service that had differed in substance from any of the others. They were all simply a matter of going through the motions, passing around the same little trays of individual cups of grape juice and broken bits of crackers, hearing the same words of institution from the man behind the communion table, doing in unison with everyone in the congregation an act which had practically no meaning to me other than as a simple reminder of what Jesus had done. Only once in my young life do I recall anything other which I was allowed to participate in. It was an Episcopal or ecumenical service where there was a common cup served at the front, and everyone filed up to receive it. That made an impression on me. More because I was grossed out about the possibility of picking up someone's germs, but that's just the mind of a kid at work. The point was, it was the first time I'd experienced something substantially different -- and thus ultimately memorable -- in a celebration of the Lord's Supper. It was to be the first of many. The next one I remember was at a Presbyterian Church in Bellevue, WA, which I visited with a friend. They had a special Maundy Thursday communion service one year. There were several stations set up around the sanctuary with tablecloths and baskets of bread and a common cup at each table. The room was in darkness except for some candle light. People gathered around the tables in groups and served the bread and the cup to each other. That communal aspect of it was very significant to me.

At Regent, the introduction of real wine instead of grape juice was a welcome change from my prior experiences of communion. We always have the option of grape juice at one of the stations, for people who are constitutionally incapable of having wine or prefer not to. But I almost always choose the wine (unless that line is too long), because there is something more powerful to me in the symbolism of real wine. I believe any liquid can work, and of course one has to use what is available given cultural limitations and all. I heard about one church in Africa that uses Kool-Aid for communion because wine and grape juice are not available. They cannot drink the water without boiling it, and even then it has a funny flavor, so they use Kool-Aid it to cover that. One time there was no Kool-Aid mix to be had, so someone had bought Jell-O powder, thinking it would do the same trick. But of course once you boil water and add Jell-O mix and then add ice cubes to cool it down, it turns into Jell-O, so it was an interesting communion service, to say the least. "This is my blood of the new covenant. Drink...er, slurp ye all of it."

I have experienced so many memorable communion services with the Regent community. There was the one which took place on a weekend class retreat. About 60-80 of us sat for our final meal at picnic-style tables that had been arranged in the shape of a cross. The Lord's Supper was celebrated as part of the meal, with bread and wine that we would finish consuming with our meat and salad, just as Jesus and his disciples would have done with the wine and bread he used as symbols on that night 2000 years ago. I loved that very down-to-earth aspect to it. Another memorable communion service was the time when the words of institution were given by someone who had grown up in a church where guilt was the motivating factor: you had to repent before approaching the table because otherwise you were not worthy to receive the elements. But of course none of us is ever "worthy" to receive the elements, and Donna told us, with tears in her eyes, that it wasn't until she got to Regent that she realized communion was a gift to us, an invitation from Jesus to the unworthy, Jesus who loved us while we were still sinners. She had never experienced communion as God's grace before.

While I agree with Sorina's comments below mine in that aforementioned post, that there can be productions that are so far away from the text that they are no longer valid (for example the controversial "milk and honey" feminist communion service at the "Reimagining Conference" in 1993), I think there is lots of room for variation in how we interpret Scripture in our "performances" of it in worship and in living. And it is such a rich text, that we will never exhaust all the possibilities. I think God, as the Audience of One, enjoys the creative ways we seek to be true to his Word while injecting newness and memorable qualities into our worship.

Do we "perform" Scripture in a way when we read it into our lives and re-enact it in worship? Are we the actors/musicians, and our pastors and biblical theologians the directors/conductors? Can there be multiple different valid "performances" Scripture? And the big question: who (or should I say Who) is the audience?I probably tipped my hand a bit too much by that parenthetical comment. Yes, I do believe God is the audience when we "perform" Scripture in our lives and worship. Not that the text of Scripture is some kind of script that we follow blindly as if our lives are completely choreographed in advance. But the stories of the biblical narrative are played out again and again in our families and communities, the psalms and anthems are sung in our worship services, and when we celebrate communion we are re-enacting the Lord's Last Supper (Catholic theologians would go so far as to say we are re-enacting the sacrifice of Christ).

As to whether there can be multiple different valid "performances" of Scripture, I think there can. Let me just take the eucharist as one small example to show how. Until I was in my 20's I had rarely experienced a communion service that had differed in substance from any of the others. They were all simply a matter of going through the motions, passing around the same little trays of individual cups of grape juice and broken bits of crackers, hearing the same words of institution from the man behind the communion table, doing in unison with everyone in the congregation an act which had practically no meaning to me other than as a simple reminder of what Jesus had done. Only once in my young life do I recall anything other which I was allowed to participate in. It was an Episcopal or ecumenical service where there was a common cup served at the front, and everyone filed up to receive it. That made an impression on me. More because I was grossed out about the possibility of picking up someone's germs, but that's just the mind of a kid at work. The point was, it was the first time I'd experienced something substantially different -- and thus ultimately memorable -- in a celebration of the Lord's Supper. It was to be the first of many. The next one I remember was at a Presbyterian Church in Bellevue, WA, which I visited with a friend. They had a special Maundy Thursday communion service one year. There were several stations set up around the sanctuary with tablecloths and baskets of bread and a common cup at each table. The room was in darkness except for some candle light. People gathered around the tables in groups and served the bread and the cup to each other. That communal aspect of it was very significant to me.

At Regent, the introduction of real wine instead of grape juice was a welcome change from my prior experiences of communion. We always have the option of grape juice at one of the stations, for people who are constitutionally incapable of having wine or prefer not to. But I almost always choose the wine (unless that line is too long), because there is something more powerful to me in the symbolism of real wine. I believe any liquid can work, and of course one has to use what is available given cultural limitations and all. I heard about one church in Africa that uses Kool-Aid for communion because wine and grape juice are not available. They cannot drink the water without boiling it, and even then it has a funny flavor, so they use Kool-Aid it to cover that. One time there was no Kool-Aid mix to be had, so someone had bought Jell-O powder, thinking it would do the same trick. But of course once you boil water and add Jell-O mix and then add ice cubes to cool it down, it turns into Jell-O, so it was an interesting communion service, to say the least. "This is my blood of the new covenant. Drink...er, slurp ye all of it."

I have experienced so many memorable communion services with the Regent community. There was the one which took place on a weekend class retreat. About 60-80 of us sat for our final meal at picnic-style tables that had been arranged in the shape of a cross. The Lord's Supper was celebrated as part of the meal, with bread and wine that we would finish consuming with our meat and salad, just as Jesus and his disciples would have done with the wine and bread he used as symbols on that night 2000 years ago. I loved that very down-to-earth aspect to it. Another memorable communion service was the time when the words of institution were given by someone who had grown up in a church where guilt was the motivating factor: you had to repent before approaching the table because otherwise you were not worthy to receive the elements. But of course none of us is ever "worthy" to receive the elements, and Donna told us, with tears in her eyes, that it wasn't until she got to Regent that she realized communion was a gift to us, an invitation from Jesus to the unworthy, Jesus who loved us while we were still sinners. She had never experienced communion as God's grace before.

While I agree with Sorina's comments below mine in that aforementioned post, that there can be productions that are so far away from the text that they are no longer valid (for example the controversial "milk and honey" feminist communion service at the "Reimagining Conference" in 1993), I think there is lots of room for variation in how we interpret Scripture in our "performances" of it in worship and in living. And it is such a rich text, that we will never exhaust all the possibilities. I think God, as the Audience of One, enjoys the creative ways we seek to be true to his Word while injecting newness and memorable qualities into our worship.

11 November 2006

Announcing new photo blog

Come visit my new photo blog, Space For God. It is a place for me to explore the beauty of God's creation, slow down enough to make space for God in my life every day, and bring some rest and inspiration to travellers who stop by.

01 November 2006

November Poem of the Month

I'm starting a new tradition, inspired by my fellow Pennsylvania poet Barbara Crooker's website, of a "poem of the month." We'll see if this really does become a tradition! Meanwhile, here's one to start with. Commentary/critique is encouraged, even requested!

The Taste of Words

To R. L., who lost his hearing at the age of seven

I have almost forgot the taste of words. They slide

As thin as colors past my tongue like light

On eyes and eyelids, or shadows gliding by

Beneath their mirror clouds, cirrus slight,

Reflections twice reflected: once, like sight,

Shone smaller in your eyes, then back in mine:

So I speak ribbon words between my ears and mind,

But barely in my mouth. I should take time to round

My palate to their shapes, their moons and ponds

Of vowels; clench their sudden curtain sounds

In stifled yawns; and run my tongue along

The lone serration at the edge of speech: a long

Delicious lingering while words melt, smooth

And butter-sweet, oh, slowly, like the way a blue tune

Seems to haze the air its own shade, and almost flavour,

Smoky, transient, intangible. You inhale no melodies,

Alas; or is it sad, or does your mind find windless pleasure

In its lagoon depths, without clamour? No screams,

No enharmonic dissonance, just what you see

And what you say, and that formed solid in the dark

Architecture of your teeth & throat, if not built in your heart.

~ Sørina Higgins

"The Taste of Words" by Sørina Higgins is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. This means that you can copy and distribute the work if you will not receive any commercial gain; that you can use the work in a new creative way (song lyrics, dramatic production, visual display), again, if you receive no commercial gain; and any other use that does not make you any money--as long as you do not change any of the words of the original text. Also, the author would like to be notified of any uses of her poem. Thank you.

The Taste of Words

To R. L., who lost his hearing at the age of seven

I have almost forgot the taste of words. They slide

As thin as colors past my tongue like light

On eyes and eyelids, or shadows gliding by

Beneath their mirror clouds, cirrus slight,

Reflections twice reflected: once, like sight,

Shone smaller in your eyes, then back in mine:

So I speak ribbon words between my ears and mind,

But barely in my mouth. I should take time to round

My palate to their shapes, their moons and ponds

Of vowels; clench their sudden curtain sounds

In stifled yawns; and run my tongue along

The lone serration at the edge of speech: a long

Delicious lingering while words melt, smooth

And butter-sweet, oh, slowly, like the way a blue tune

Seems to haze the air its own shade, and almost flavour,

Smoky, transient, intangible. You inhale no melodies,

Alas; or is it sad, or does your mind find windless pleasure

In its lagoon depths, without clamour? No screams,

No enharmonic dissonance, just what you see

And what you say, and that formed solid in the dark

Architecture of your teeth & throat, if not built in your heart.

~ Sørina Higgins

"The Taste of Words" by Sørina Higgins is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. This means that you can copy and distribute the work if you will not receive any commercial gain; that you can use the work in a new creative way (song lyrics, dramatic production, visual display), again, if you receive no commercial gain; and any other use that does not make you any money--as long as you do not change any of the words of the original text. Also, the author would like to be notified of any uses of her poem. Thank you.

"Art is God made visible"

Listened to: Revival in Belfast (Robin Mark CD)

I'm reading a book called House of Belief: Creating Your Personal Style by Kelee Katillac. It's an interior designer's ideas on how to make the decor in your house reflect your personal beliefs and values. She feels it's important to do this because what we see around us reinforces what we believe. In one chapter, "The Church of the Home," she tells of how in times past, cathedrals provided those "visual affirmations" for believers. Describing a visit to Notre Dame, she writes, "the vaulting, the very architecture of the place--the great church in its physical form--suggests man embracing God. The central hall, or nave, with its right and left wings, forms the shape of a human body with torso and arms stretched outward--arms open to receive divine inspiration, baring the soul to receive the secrets of creation. [The shape of a cross, too, I might add, which not coincidentally happens to fit a human body.] Like priests performing a transforming ritual, the craftsmen forged their beliefs into works of artistry. Wood and stone were transformed into a body of belief with a rib cage of great buttresses, leglike pillars, and a heart of carved altars. All around me...I could see...evidence of God, not as remote or detached but as present and active, communing with man in a sort of divine collaboration....There in the brushstrokes of a mural and in the deep carvings of marble statuary I could see something of God's own creative nature as it has been emulated through artistic expression. Art is God made visible."

This is another example of what Admonit was talking about in her Embodied Theology post.

I'm reading a book called House of Belief: Creating Your Personal Style by Kelee Katillac. It's an interior designer's ideas on how to make the decor in your house reflect your personal beliefs and values. She feels it's important to do this because what we see around us reinforces what we believe. In one chapter, "The Church of the Home," she tells of how in times past, cathedrals provided those "visual affirmations" for believers. Describing a visit to Notre Dame, she writes, "the vaulting, the very architecture of the place--the great church in its physical form--suggests man embracing God. The central hall, or nave, with its right and left wings, forms the shape of a human body with torso and arms stretched outward--arms open to receive divine inspiration, baring the soul to receive the secrets of creation. [The shape of a cross, too, I might add, which not coincidentally happens to fit a human body.] Like priests performing a transforming ritual, the craftsmen forged their beliefs into works of artistry. Wood and stone were transformed into a body of belief with a rib cage of great buttresses, leglike pillars, and a heart of carved altars. All around me...I could see...evidence of God, not as remote or detached but as present and active, communing with man in a sort of divine collaboration....There in the brushstrokes of a mural and in the deep carvings of marble statuary I could see something of God's own creative nature as it has been emulated through artistic expression. Art is God made visible."

This is another example of what Admonit was talking about in her Embodied Theology post.

31 October 2006

Another take on the old "What Is Art?" question

A friend of mine, Paul Butzi, is a photographer. You can see some of his excellent work at his website. He also has a blog there, where he posted this interesting musing on whether the question "What Is Art?" is worth asking at all. Essentially it boils down to what he calls "Paul's Rule": "never ask a question unless you're going to change your behavior based on the answer." He wouldn't stop making photography if it turned out it wasn't art, so perhaps it's not important to know the answer. There's a great story in his post about Jean-Pierre Rampal and a mockingbird, so go read it.

29 October 2006

To Adapt or Not to Adapt

...and that's only the beginning of the question...

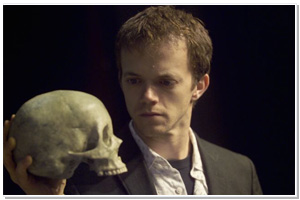

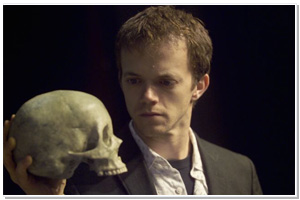

Christopher Yeatts as Hamlet in the Pennsylvania Shakespeare Festival WillPower touring production of Hamlet.

Read: Lilith by George MacDonald.

Watched: A one-hour-and-twenty-minute version of Hamlet by members of the Pennsylvania Shakespeare Festival and a “traditional” performance of King Lear by the theatre department of Northampton Community College.

Listened to: lots of Beatles albums, Bach, Chopin, & contemporary Native American singer/songwriters.

I’ve been wondering about adaptations recently. Here’s the question I’d like readers to answer: Do you hold a sort of “sacrosanct” view of texts, that is, that they should never be adapted, or do you think that anything written is available for change & re-presentation? I’m thinking especially of plays, but this conversation could be relevant for music, books-to-movies, etc. So, do you think that an artist’s original work should stand as it is, or could & should it be adapted to suit the mood of the times? Do you think any “real” presentation of a work is possible when moving from one medium to another, such as page-to-stage, page-to-screen, and so forth?

So, that’s it. That’s my question. But that said, of course I have to go on and give my opinion. First of all, let’s just make it clear that we’re not talking about copyright violations. Let’s assume that the material we’ll discuss is either in the public domain or the adaptor has received permission to do whatever hacking, cutting, and pasting s/he may desire.

I used to believe that any text, or indeed any original work of art, was almost sacred, that it should not be touched or changed at all. I was horrified by The Lord of the Rings when it first came out, due to the drastic changes the director made. He ruined Faramir’s character, changed some crucial speeches, and left out the last sixth of the book! Good grief. Well, now I love those movies for their own sake, but still feel a bit of sinking sickness when I think of all the viewers who may never read the books and will always have the wrong impression. I had a similar reaction to “Narnia” an a first viewing. How dare he change nearly every word of the original book & turn it into a fairly lousy screenplay & throw in some retarded scene of cheesy drama on the ice and leave out the Emperor-Beyond-the-Sea & the Deep Magic from before the Dawn of Time, and why were the children whining to go home all the time? You can see I’m rather passionate about this, still. Even though I appreciate those movies for their own sake, as great movies, I shudder when I think of them as visual representations of the books.

But recently I’ve been developing a new attitude towards adaptations. It began this summer in Oxford, when my prof. Emma Smith said many times that she thought the best directors of Shakespeare were those who were not afraid to cut, paste, change, hack, chop, and disfigure to their hearts’ content. Well, she didn’t exactly say it like that, but that was the idea. Her premise seemed to be that any new production of an old play is a work of art in its own right, and must change with the times/places to be relevant, fresh, and compelling. And I’m beginning to agree with her.

The production of Hamlet by the traveling troupe from the Pennsylvania Shakespeare Festival was extraordinary—very dynamic, very alive, very relevant, and totally exciting. Hamlet dressed in black, of course, but it was black jeans & worn dress shirt & ill-tied tie. The set was like Hot Topic or a Goth-style artist’s flat in Harlem: faded purple & black velvet draped across the back, with well-chosen graffiti scrawled across it: “Remember Me” and “Dust” were most predominant. Ophelia was hovering between a Goth look—black net tights, black tank top over ruffled white dress—and girly-cutsie—pink ballet shoes and a flower in her hair. Clearly, they were teenagers going through identity crises. Claudius and Gertrude, on the other hand, were stiff and business-like, with a roaring-Twenties touch, putting them very far out of touch with Hamlet’s uncertain and artistic world. The ghost’s appearance was accompanied by “Mission: Impossible” or James Bond theme-song kind of music, fast, intense, and supremely modern. One of the guards was a girl, dressed in grey spandex, and all those on watch squatted on the alert with flashlights poised. Think Charlie’s Angels. Very slick, very NOW.

When Hamlet went into his little madness game, he shuffled out wearing a T-shirt that hung to his knees, sneakers about two feet long with their white tongues sticking up, a huge white baseball cap on sideways, and a Sponge Bob necklace. He held his book with the spine perpendicular to his hands, and looked for all the world like a cartoon character.

Oh, and did I mention that the production was 80 minutes long? About maybe 1/3 of the text was presented.

My point in relating all these details is this. I’m coming to think that in the fluid medium of live theatre, adaptations should be just that: adaptations. OED says that “adapt” means “make suitable for a new use or purpose” or “become adjusted to new conditions.” [Thank you, OED.] Shakespeare’s plays have been performed innumerable times. And no one performance on stage can possibly claim to be THE ONE AND ONLY definitive performance that interprets every possible detail according to—what? Shakespeare’s intention? Original performance practice? Elizabethan or Jacobean conditions? The ideal hidden meaning expressed in the outward form? No sir-ee. Each production is a new, fresh perspective, yet another way to look at the play. So I’m starting to think, adapt as you will!

Now, that’s what I think about the fluid medium of theatre. Films, I believe, are in a different category. This is because films are static. Once it’s been filmed, that’s it. OK, sure, so they can release the special edition extended version DVD, and I’m glad when they do (waiting for the “Lion, Witch, & Wardrobe” extended to see what they left out—or in, depending on how you look at that). But even so, that’s fixed. So it does, then purport to be at least a definitive version, if not THE one and only. So, back to LOTR. I’m disturbed by how much was left out & changed of that book/epic/series/triliogy/quadrilogy. Wait, it’s not a quadrilogy yet. Has anyone heard if they are indeed making The Hobbit with what’s-his-name Elijah Wood as Bilbo? Because of the great technology, etc., this film is almost worthy of its literary prototype. Almost. And I’m afraid that it will stand in for the thing itself. So I think that when directors are re-making a masterpiece in a static medium such as film, it behooves them to be as true to the original as possible.

But who knows, maybe one day film too will be somehow a fluid medium, and there will as many LOTRs made as Romeo & Juliets. Who knows. And would that be good or bad?

Christopher Yeatts as Hamlet in the Pennsylvania Shakespeare Festival WillPower touring production of Hamlet.

Read: Lilith by George MacDonald.

Watched: A one-hour-and-twenty-minute version of Hamlet by members of the Pennsylvania Shakespeare Festival and a “traditional” performance of King Lear by the theatre department of Northampton Community College.

Listened to: lots of Beatles albums, Bach, Chopin, & contemporary Native American singer/songwriters.

I’ve been wondering about adaptations recently. Here’s the question I’d like readers to answer: Do you hold a sort of “sacrosanct” view of texts, that is, that they should never be adapted, or do you think that anything written is available for change & re-presentation? I’m thinking especially of plays, but this conversation could be relevant for music, books-to-movies, etc. So, do you think that an artist’s original work should stand as it is, or could & should it be adapted to suit the mood of the times? Do you think any “real” presentation of a work is possible when moving from one medium to another, such as page-to-stage, page-to-screen, and so forth?

So, that’s it. That’s my question. But that said, of course I have to go on and give my opinion. First of all, let’s just make it clear that we’re not talking about copyright violations. Let’s assume that the material we’ll discuss is either in the public domain or the adaptor has received permission to do whatever hacking, cutting, and pasting s/he may desire.

I used to believe that any text, or indeed any original work of art, was almost sacred, that it should not be touched or changed at all. I was horrified by The Lord of the Rings when it first came out, due to the drastic changes the director made. He ruined Faramir’s character, changed some crucial speeches, and left out the last sixth of the book! Good grief. Well, now I love those movies for their own sake, but still feel a bit of sinking sickness when I think of all the viewers who may never read the books and will always have the wrong impression. I had a similar reaction to “Narnia” an a first viewing. How dare he change nearly every word of the original book & turn it into a fairly lousy screenplay & throw in some retarded scene of cheesy drama on the ice and leave out the Emperor-Beyond-the-Sea & the Deep Magic from before the Dawn of Time, and why were the children whining to go home all the time? You can see I’m rather passionate about this, still. Even though I appreciate those movies for their own sake, as great movies, I shudder when I think of them as visual representations of the books.

But recently I’ve been developing a new attitude towards adaptations. It began this summer in Oxford, when my prof. Emma Smith said many times that she thought the best directors of Shakespeare were those who were not afraid to cut, paste, change, hack, chop, and disfigure to their hearts’ content. Well, she didn’t exactly say it like that, but that was the idea. Her premise seemed to be that any new production of an old play is a work of art in its own right, and must change with the times/places to be relevant, fresh, and compelling. And I’m beginning to agree with her.

The production of Hamlet by the traveling troupe from the Pennsylvania Shakespeare Festival was extraordinary—very dynamic, very alive, very relevant, and totally exciting. Hamlet dressed in black, of course, but it was black jeans & worn dress shirt & ill-tied tie. The set was like Hot Topic or a Goth-style artist’s flat in Harlem: faded purple & black velvet draped across the back, with well-chosen graffiti scrawled across it: “Remember Me” and “Dust” were most predominant. Ophelia was hovering between a Goth look—black net tights, black tank top over ruffled white dress—and girly-cutsie—pink ballet shoes and a flower in her hair. Clearly, they were teenagers going through identity crises. Claudius and Gertrude, on the other hand, were stiff and business-like, with a roaring-Twenties touch, putting them very far out of touch with Hamlet’s uncertain and artistic world. The ghost’s appearance was accompanied by “Mission: Impossible” or James Bond theme-song kind of music, fast, intense, and supremely modern. One of the guards was a girl, dressed in grey spandex, and all those on watch squatted on the alert with flashlights poised. Think Charlie’s Angels. Very slick, very NOW.

When Hamlet went into his little madness game, he shuffled out wearing a T-shirt that hung to his knees, sneakers about two feet long with their white tongues sticking up, a huge white baseball cap on sideways, and a Sponge Bob necklace. He held his book with the spine perpendicular to his hands, and looked for all the world like a cartoon character.

Oh, and did I mention that the production was 80 minutes long? About maybe 1/3 of the text was presented.

My point in relating all these details is this. I’m coming to think that in the fluid medium of live theatre, adaptations should be just that: adaptations. OED says that “adapt” means “make suitable for a new use or purpose” or “become adjusted to new conditions.” [Thank you, OED.] Shakespeare’s plays have been performed innumerable times. And no one performance on stage can possibly claim to be THE ONE AND ONLY definitive performance that interprets every possible detail according to—what? Shakespeare’s intention? Original performance practice? Elizabethan or Jacobean conditions? The ideal hidden meaning expressed in the outward form? No sir-ee. Each production is a new, fresh perspective, yet another way to look at the play. So I’m starting to think, adapt as you will!

Now, that’s what I think about the fluid medium of theatre. Films, I believe, are in a different category. This is because films are static. Once it’s been filmed, that’s it. OK, sure, so they can release the special edition extended version DVD, and I’m glad when they do (waiting for the “Lion, Witch, & Wardrobe” extended to see what they left out—or in, depending on how you look at that). But even so, that’s fixed. So it does, then purport to be at least a definitive version, if not THE one and only. So, back to LOTR. I’m disturbed by how much was left out & changed of that book/epic/series/triliogy/quadrilogy. Wait, it’s not a quadrilogy yet. Has anyone heard if they are indeed making The Hobbit with what’s-his-name Elijah Wood as Bilbo? Because of the great technology, etc., this film is almost worthy of its literary prototype. Almost. And I’m afraid that it will stand in for the thing itself. So I think that when directors are re-making a masterpiece in a static medium such as film, it behooves them to be as true to the original as possible.

But who knows, maybe one day film too will be somehow a fluid medium, and there will as many LOTRs made as Romeo & Juliets. Who knows. And would that be good or bad?

15 October 2006

Herbert and "Embodied Theology"

Read: Several chapters into Don Quixote

Listened to: Tannhäuser (Wagner), “Amadeus” soundtrack

Watched: at least part of if not most of: City Lights (Charlie Chaplin), The General (Buster Keaton), Sunrise (F.W. Murnau), M (Fritz Lang), and Citizen Kane (Orson Welles) [all for the film class I'm taking]

This started out as a comment on Sorina’s previous post, but it began to get long enough that I decided to promote it to a post in its own right. I’ve been waiting to let Sorina’s students get a chance to post comments first, but seeing that no one has taken the bait (yet), and I’m chomping at the bit to comment on this one, I’m not going to wait any longer.

I had the pleasure of taking a whole class on the metaphysical poets, particularly Donne and Herbert, at Regent College several summers ago. Herbert is among my top five poets, if not my favorite (depending on my mood).

As for his use of poetic form, Herbert is more creative in inventing new forms than he is strictly adhering to existing forms. Over two-thirds of the poems in his collection The Temple are in a unique meter and rhyme scheme. He plays around with varying line lengths, lots of word play, anagrams (“Anagram”), concrete poetry where the physical shape of the poem on the page relates to the content (“The Altar,” “Easter Wings”), and cross-references between adjacent poems (e.g., a word in the last line of a poem which is taken up in the first line of the next, or the title of a poem which takes up the theme of the preceding one). It is sheer fun to read his poems and discover all his delightful frolicking. And yet, as you pointed out, he wrestled with whether these frills were appropriate for the serious genre of sacred poetry.

However, I disagree with your reading of “Jordan (2).” First, you’ll have to be more specific about what “aspects of Sidney’s secular love sonnet” Herbert is copying. I don’t see the resemblance in form at all. Second, when Herbert writes “There is in love a sweetness ready penn’d: Copy out only that,...” you’ve got to see it in the context of Herbert’s own poetry -- both this very poem, and his whole oeuvre. He begins “When first my lines of heav’nly joys made mention.” So I don’t believe he’s talking about secular love in line 17, but rather about his devotion to God (as in so many of his poems). I think he simply means to exhort himself (the “friend” in line 15 is merely his own conscience speaking to him): “just say plainly what’s written on your heart, and leave all this decorative poetic inventiveness aside, as it only feeds your pride.” But of course he cannot make himself do that and ends up with another poem that’s just as creative as the last. And we, from our vantage point, realize that Herbert was carrying out his vocation from God and needn’t have beaten himself up over his desire to use artistry in his writing.

As for how Herbert uses poetic form to express his theology:

The ordering of the poems in The Temple is ingenious, and speaks of Herbert’s ecclesiology. Overall, the structure is reminiscent of church architecture, with an entrance through “The Church-Porch,” the opening poem. Then the main body of The Temple is called “The Church,” with an introductory poem called “The Altar.” Of course the altar or communion table would have been a focal point in the interior of an English church in his era. Later there is a series of poems with titles depicting other parts of a church, e.g., “The Church-floor” and “The Windows.” Other parts of the collection are organized around liturgical themes and the church year.

Herbert sometimes uses the number of lines per stanza with significance, as in “Sunday” where there are seven lines per stanza, representing the seventh day, and “Trinity Sunday” where there are three stanzas with three lines each. In “Coloss 3.3” he hides a Bible verse along the diagonal, “My life is hid in Him that is my treasure,” displaying concretely what it is to be “hid with Christ in God.”

That’s enough on Herbert, but I would venture to propose that even Scripture itself uses poetic devices to convey theological meaning. Understanding something about the literary techniques employed in great poetry and literature will help in interpreting the Bible. Some would balk at the idea of “reading the Bible as literature” because it seems to be mutually exclusive with reading it as the Word of God; as if “literature” meant something invented out of whole cloth by humans. And indeed many (if not most) college courses that purport to teach the “Bible as literature” are taught by people who think it is only that. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t onto something with regard to the incredible artistry with which the Bible is crafted. And if human artists can embed their theology in their work, as Sorina’s posts are beginning to convince us, how much more can the Artist of Artists do that, through the pens of his intelligent creatures?

Listened to: Tannhäuser (Wagner), “Amadeus” soundtrack

Watched: at least part of if not most of: City Lights (Charlie Chaplin), The General (Buster Keaton), Sunrise (F.W. Murnau), M (Fritz Lang), and Citizen Kane (Orson Welles) [all for the film class I'm taking]

This started out as a comment on Sorina’s previous post, but it began to get long enough that I decided to promote it to a post in its own right. I’ve been waiting to let Sorina’s students get a chance to post comments first, but seeing that no one has taken the bait (yet), and I’m chomping at the bit to comment on this one, I’m not going to wait any longer.

I had the pleasure of taking a whole class on the metaphysical poets, particularly Donne and Herbert, at Regent College several summers ago. Herbert is among my top five poets, if not my favorite (depending on my mood).

As for his use of poetic form, Herbert is more creative in inventing new forms than he is strictly adhering to existing forms. Over two-thirds of the poems in his collection The Temple are in a unique meter and rhyme scheme. He plays around with varying line lengths, lots of word play, anagrams (“Anagram”), concrete poetry where the physical shape of the poem on the page relates to the content (“The Altar,” “Easter Wings”), and cross-references between adjacent poems (e.g., a word in the last line of a poem which is taken up in the first line of the next, or the title of a poem which takes up the theme of the preceding one). It is sheer fun to read his poems and discover all his delightful frolicking. And yet, as you pointed out, he wrestled with whether these frills were appropriate for the serious genre of sacred poetry.

However, I disagree with your reading of “Jordan (2).” First, you’ll have to be more specific about what “aspects of Sidney’s secular love sonnet” Herbert is copying. I don’t see the resemblance in form at all. Second, when Herbert writes “There is in love a sweetness ready penn’d: Copy out only that,...” you’ve got to see it in the context of Herbert’s own poetry -- both this very poem, and his whole oeuvre. He begins “When first my lines of heav’nly joys made mention.” So I don’t believe he’s talking about secular love in line 17, but rather about his devotion to God (as in so many of his poems). I think he simply means to exhort himself (the “friend” in line 15 is merely his own conscience speaking to him): “just say plainly what’s written on your heart, and leave all this decorative poetic inventiveness aside, as it only feeds your pride.” But of course he cannot make himself do that and ends up with another poem that’s just as creative as the last. And we, from our vantage point, realize that Herbert was carrying out his vocation from God and needn’t have beaten himself up over his desire to use artistry in his writing.

As for how Herbert uses poetic form to express his theology:

The ordering of the poems in The Temple is ingenious, and speaks of Herbert’s ecclesiology. Overall, the structure is reminiscent of church architecture, with an entrance through “The Church-Porch,” the opening poem. Then the main body of The Temple is called “The Church,” with an introductory poem called “The Altar.” Of course the altar or communion table would have been a focal point in the interior of an English church in his era. Later there is a series of poems with titles depicting other parts of a church, e.g., “The Church-floor” and “The Windows.” Other parts of the collection are organized around liturgical themes and the church year.

Herbert sometimes uses the number of lines per stanza with significance, as in “Sunday” where there are seven lines per stanza, representing the seventh day, and “Trinity Sunday” where there are three stanzas with three lines each. In “Coloss 3.3” he hides a Bible verse along the diagonal, “My life is hid in Him that is my treasure,” displaying concretely what it is to be “hid with Christ in God.”

That’s enough on Herbert, but I would venture to propose that even Scripture itself uses poetic devices to convey theological meaning. Understanding something about the literary techniques employed in great poetry and literature will help in interpreting the Bible. Some would balk at the idea of “reading the Bible as literature” because it seems to be mutually exclusive with reading it as the Word of God; as if “literature” meant something invented out of whole cloth by humans. And indeed many (if not most) college courses that purport to teach the “Bible as literature” are taught by people who think it is only that. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t onto something with regard to the incredible artistry with which the Bible is crafted. And if human artists can embed their theology in their work, as Sorina’s posts are beginning to convince us, how much more can the Artist of Artists do that, through the pens of his intelligent creatures?

08 October 2006

Milton & the Metaphysical Poets

Read: Phantastes by George MacDonald.

Watched: Cromwell

Listened to: student rap versions of hymns by Isaac Watts & Charles Wesley!!

In a previous post I discussed what I called Bach’s “Embodied Theology”—some of the ways in which Bach expressed his doctrinal beliefs in the very arrangement of notes, rhythms, etc. in his music. Now in this post I’d like to explore something similar in the poetry of John Milton & the “Metaphysical Poets,” especially George Herbert & John Donne, and I’d like my students (and any other readers) to add their thoughts.

There are two ways in which I see Milton, Donne, & Herbert embodying their theology in their works: 1. form & 2. technique. First, poetic form—the shapes they gave to their works. The fact that they chose to use standard, strict forms such as sonnet & epic shows, I think, that they believed the universe was an orderly place. They believed that nature revealed God’s love of organization, structure, and symmetry, so they chose highly organized poetic forms—with some notable exceptions. They also thought, I imagine, that working within boundaries is the best kind of freedom. Only within moral boundaries are people truly free to live & love; only within strict poetry boundaries like 14 lines, iambic pentameter, ababcdcdefefgg rhyme scheme, and so on, is the poet free to be truly creative (again, there are significant exceptions to this rule, and I’ll discuss at least one). That’s one idea the shapes of their poems gives me.

Form works on a larger scale, too. Paradise Lost is in 12 “books”—again, an orderly structure, and one that can have spiritual significance. 12 tribes of Israel, 12 apostles, 12-sided wall around the new Jerusalem, 12 jewels set over the 12 gates…. And Herbert takes form even a step further, using it to interpret & interrogate the meanings of his poems. In “Jordan (2)” (which we did not read in class; but you can find it here), Herbert copies aspects of Sidney’s secular love sonnet, "Loving in Truth", but says that it’s sinful to write decorative sacred poetry, and then ends by implying that all you can do is copy secular love poetry! So he simultaneously condemns & commends himself for using Sidney’s form, and does so by means of the form! He does something similar with the form of “The Wreath,” which perhaps one of my diligent students would explain below? (It would be good practice for the test that’s coming up, hint, hint…).

And the second way I see them working their theology into their poetry is in some of the specific poetic techniques—meter, rhyme, alliteration, etc. Let’s look at Donne’s "Batter My Heart" as an example. In line 4, he says he wants God to “break, blow, burn, and make me new.” Well, he does just that to the poetry! Instead of following the standard - / - / - / - / - / pattern of iambic pentameter, he “breaks” it with a series of strong monosyllables, all alliterating on one of the harshest consonants—to illustrate just how he wants God to pound on his stubborn heart! Another example occurs in Herbert’s “The Wreath” , when Herbert messes up his habitual pattern with the words “crooked winding ways”—illustrating the fact that his sin has messed up his life so badly it’s even messed up the patterns in his poetry! And he does this again on a large scale with the beginning and ending of his poem, which again perhaps a student would explain in a comment? And Milton even uses the complexity of his syntax & the length of his sentences to express the high, lofty, & complicated nature of the spiritual history he’s giving in Paradise Lost.

So now that you (hopefully) understand this idea of embodying doctrinal beliefs in verse, perhaps you can put in some observations of your own. They could be about the 17th century poets, or about any other writers. Or, as always, I’d really love to see examples of other genres (visual arts, music, etc.) that use similar techniques.

Watched: Cromwell

Listened to: student rap versions of hymns by Isaac Watts & Charles Wesley!!

In a previous post I discussed what I called Bach’s “Embodied Theology”—some of the ways in which Bach expressed his doctrinal beliefs in the very arrangement of notes, rhythms, etc. in his music. Now in this post I’d like to explore something similar in the poetry of John Milton & the “Metaphysical Poets,” especially George Herbert & John Donne, and I’d like my students (and any other readers) to add their thoughts.

There are two ways in which I see Milton, Donne, & Herbert embodying their theology in their works: 1. form & 2. technique. First, poetic form—the shapes they gave to their works. The fact that they chose to use standard, strict forms such as sonnet & epic shows, I think, that they believed the universe was an orderly place. They believed that nature revealed God’s love of organization, structure, and symmetry, so they chose highly organized poetic forms—with some notable exceptions. They also thought, I imagine, that working within boundaries is the best kind of freedom. Only within moral boundaries are people truly free to live & love; only within strict poetry boundaries like 14 lines, iambic pentameter, ababcdcdefefgg rhyme scheme, and so on, is the poet free to be truly creative (again, there are significant exceptions to this rule, and I’ll discuss at least one). That’s one idea the shapes of their poems gives me.

Form works on a larger scale, too. Paradise Lost is in 12 “books”—again, an orderly structure, and one that can have spiritual significance. 12 tribes of Israel, 12 apostles, 12-sided wall around the new Jerusalem, 12 jewels set over the 12 gates…. And Herbert takes form even a step further, using it to interpret & interrogate the meanings of his poems. In “Jordan (2)” (which we did not read in class; but you can find it here), Herbert copies aspects of Sidney’s secular love sonnet, "Loving in Truth", but says that it’s sinful to write decorative sacred poetry, and then ends by implying that all you can do is copy secular love poetry! So he simultaneously condemns & commends himself for using Sidney’s form, and does so by means of the form! He does something similar with the form of “The Wreath,” which perhaps one of my diligent students would explain below? (It would be good practice for the test that’s coming up, hint, hint…).

And the second way I see them working their theology into their poetry is in some of the specific poetic techniques—meter, rhyme, alliteration, etc. Let’s look at Donne’s "Batter My Heart" as an example. In line 4, he says he wants God to “break, blow, burn, and make me new.” Well, he does just that to the poetry! Instead of following the standard - / - / - / - / - / pattern of iambic pentameter, he “breaks” it with a series of strong monosyllables, all alliterating on one of the harshest consonants—to illustrate just how he wants God to pound on his stubborn heart! Another example occurs in Herbert’s “The Wreath” , when Herbert messes up his habitual pattern with the words “crooked winding ways”—illustrating the fact that his sin has messed up his life so badly it’s even messed up the patterns in his poetry! And he does this again on a large scale with the beginning and ending of his poem, which again perhaps a student would explain in a comment? And Milton even uses the complexity of his syntax & the length of his sentences to express the high, lofty, & complicated nature of the spiritual history he’s giving in Paradise Lost.

So now that you (hopefully) understand this idea of embodying doctrinal beliefs in verse, perhaps you can put in some observations of your own. They could be about the 17th century poets, or about any other writers. Or, as always, I’d really love to see examples of other genres (visual arts, music, etc.) that use similar techniques.

19 September 2006

Unfinished Tolkien work to be published

This is interesting news: J.R.R. Tolkien's son Christopher has finished a book his father began but never completed, The Children of Hurin. It will be published in 2007. Given that the younger Tolkien has been working on this for the past 30 years, I wonder how much of the work is his father's and how much is his. Nevertheless, fans of Middle Earth will surely go nuts over another story about the elves and dwarves from LOTR. CNN story.

13 September 2006

Macbeth and Predestination

Read: C. S. Lewis: A Biography by Roger Lancelyn Green & Walter Hooper.

Watched: the first part of HBO’s Elizabeth I

This is a re-hash of a previous post. My students & I have been exploring this topic in Language Arts classes recently, so I repost it here for their sakes, looking forward to their comments.