Larry Lipkis, “Maestranza,” 12 & 13 February

Doug Ovens, “Endless Possibilities,” 12 & 13 March

Paul Salerni, “Concert Fanfare,” 16 & 17 April

In this interview, we follow several threads of conversation that are becoming themes in my talks with composers: the growing importance of film (and video game) music, the continued move away from atonal music back into concepts of a center and of thematic development, and the necessity of direct communication with one’s audience. Larry also draws a brilliant comparison between music and rhetoric. Enjoy.

Please take a moment to peruse the INTRODUCTION AND INDEX to this series.

Interview with Larry Lipkis, composer

in his office at Moravian College,

17 September 2010

IA: Why don’t we start out by talking about some of your current projects, and then past projects, and so on. This year is the Allentown Symphony’s 60th anniversary, and they’re commissioning five fanfares, one for each of their concerts. Would you like to start out talking about the fanfare for the Allentown Symphony?

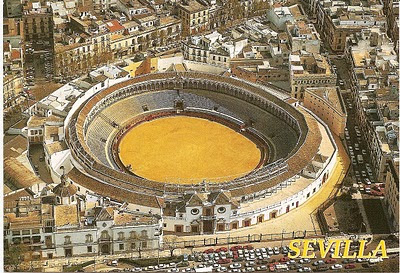

IA: Why don’t we start out by talking about some of your current projects, and then past projects, and so on. This year is the Allentown Symphony’s 60th anniversary, and they’re commissioning five fanfares, one for each of their concerts. Would you like to start out talking about the fanfare for the Allentown Symphony? LL: Sure, we can talk about that. When I was first commissioned, I wanted to see what I saw paired with, because I thought the fanfare might be something that could relate to the main piece or the main pieces on the program. So I learned to my great delight that the feature was highlights from the opera Carmen, one of my favorite operas! So there will be my fanfare, and then the rest of the program will be given over to Carmen. I began thinking along those lines: What would be a nice piece to be appropriate for that context, that wouldn’t create any dissonance with the piece but would fit in harmoniously? I didn’t want to write a pseudo-Carmen or anything like that, but I thought about the idea that Carmen is set in Spain and centered around bullfighting. I began looking at some images of bullfighting rings, actually. The whole last act of Carmen takes place in front of a big bullring in Seville. The famous bullring there is called Maestranza. So I just downloaded some images. This is what a bullring looks like:

LL: Sure, we can talk about that. When I was first commissioned, I wanted to see what I saw paired with, because I thought the fanfare might be something that could relate to the main piece or the main pieces on the program. So I learned to my great delight that the feature was highlights from the opera Carmen, one of my favorite operas! So there will be my fanfare, and then the rest of the program will be given over to Carmen. I began thinking along those lines: What would be a nice piece to be appropriate for that context, that wouldn’t create any dissonance with the piece but would fit in harmoniously? I didn’t want to write a pseudo-Carmen or anything like that, but I thought about the idea that Carmen is set in Spain and centered around bullfighting. I began looking at some images of bullfighting rings, actually. The whole last act of Carmen takes place in front of a big bullring in Seville. The famous bullring there is called Maestranza. So I just downloaded some images. This is what a bullring looks like: IA: It’s huge!

IA: It’s huge! LL: Maybe not as big as Beaver Stadium at Penn State, but not too far off. I began to think about that in terms of compositional ideas. I thought it might be interesting to turn Symphony Hall into a bullring. That means the audience would be in the middle, and the players would surround the audience to create a ring-like quality. That was one image that came to mind. I went to Allentown Symphony Hall. I have been there many times, but I really wanted to scope it out in terms of the physical space and where I might put instruments. I looked things over and I came up with a little chart that I will show you. This is my little bullring here. The audience is here [in the “orchestra” seats]; here’s the balcony; here’s the stage; and this would be the conductor. I have strings, harp, and percussion [on stage]. Then we have a little mezzanine, so if you’re walking in the mezzanine to your left, I have a choir of woodwinds: flute, oboe, clarinet and bassoon; and opposite, the other choir of woodwinds. Now we’re up in the balcony, and there’s actually plenty of room for this, so we have two horns here, two horns here, two trombones, tuba, and the trumpets in the back.

LL: Maybe not as big as Beaver Stadium at Penn State, but not too far off. I began to think about that in terms of compositional ideas. I thought it might be interesting to turn Symphony Hall into a bullring. That means the audience would be in the middle, and the players would surround the audience to create a ring-like quality. That was one image that came to mind. I went to Allentown Symphony Hall. I have been there many times, but I really wanted to scope it out in terms of the physical space and where I might put instruments. I looked things over and I came up with a little chart that I will show you. This is my little bullring here. The audience is here [in the “orchestra” seats]; here’s the balcony; here’s the stage; and this would be the conductor. I have strings, harp, and percussion [on stage]. Then we have a little mezzanine, so if you’re walking in the mezzanine to your left, I have a choir of woodwinds: flute, oboe, clarinet and bassoon; and opposite, the other choir of woodwinds. Now we’re up in the balcony, and there’s actually plenty of room for this, so we have two horns here, two horns here, two trombones, tuba, and the trumpets in the back. There is some precedent for this; I’m not the first composer to move instruments around. Actually, last year I went to an ASO concert at which they played Respighi’s “Pines of Rome,” which calls for some brass back in the balcony. But I thought getting the ring idea opened up some new possibilities.

There is some precedent for this; I’m not the first composer to move instruments around. Actually, last year I went to an ASO concert at which they played Respighi’s “Pines of Rome,” which calls for some brass back in the balcony. But I thought getting the ring idea opened up some new possibilities. IA: So is your audience the bull, or the matador? Or both?!

IA: So is your audience the bull, or the matador? Or both?! LL: Exactly! Well, maybe a little of both. I don’t want to take the analogy too literally! I’m just trying to create a ring of sound, basically.

LL: Exactly! Well, maybe a little of both. I don’t want to take the analogy too literally! I’m just trying to create a ring of sound, basically. IA: Do you use that concept musically—do harmonic progressions chase their way around the ring, or do melodies run around the circle?

IA: Do you use that concept musically—do harmonic progressions chase their way around the ring, or do melodies run around the circle? LL: In a sense. Yes. The other image that came to mind is the arch, because you can see around the perimeter of the ring there are all these arches. And of course arches are related to a ring in that they are a curved space. That also played into my ideas.

LL: In a sense. Yes. The other image that came to mind is the arch, because you can see around the perimeter of the ring there are all these arches. And of course arches are related to a ring in that they are a curved space. That also played into my ideas.

There are little arch-like musical cells. The score has many examples throughout of that kind of thing. And then, you mentioned the harmonic idea of the arch. There is one place towards the end where I thought it would be fun to get a wave of sound going one way and then back. If you’ve been to baseball games, football games: sometimes in a stadium they do the wave; people stand up, then the next section carries it on. I thought it would be fun to create a wave. At one point there is playing a static chord up here in the strings, I have a little sound idea that moves, then moves back. Musically it is in the form of a suspension: a dissonance that hovers, then resolves down. [he plays it for me]. That’s kind of a fun thing to do; the audience will be following it around.

IA: I can picture the way the noise of the crowd follows the action that’s going on in the ring; I can imagine that the fight is moving around part of the ring and back again.

IA: I can picture the way the noise of the crowd follows the action that’s going on in the ring; I can imagine that the fight is moving around part of the ring and back again. LL: Yes. I’m not literally trying to recreate a bullfight here; it’s just kind of getting some bullfight ideas into a piece of music which still has a fanfare connotation.

LL: Yes. I’m not literally trying to recreate a bullfight here; it’s just kind of getting some bullfight ideas into a piece of music which still has a fanfare connotation. IA: Are there Spanish-sounding harmonies?

IA: Are there Spanish-sounding harmonies? LL: A little bit. Not too much, but a little bit. I played through some parts of Carmen just to get that sound. I didn’t want to write faux-Spanish music, but on the other hand [he plays a selection], that has a sort of flamenco sound. It ends with just the brass at the end.

LL: A little bit. Not too much, but a little bit. I played through some parts of Carmen just to get that sound. I didn’t want to write faux-Spanish music, but on the other hand [he plays a selection], that has a sort of flamenco sound. It ends with just the brass at the end.[Then he played the MIDI file of the entire composition, as it then existed, for me.]

IA: I love the energy of it, I love the rhythms—

IA: I love the energy of it, I love the rhythms— LL: You can see, though, it is a a huge space, and it’s Diane Wittry’s job have to hold it all together! I met with her and showed her the score. She is great and she loves a challenge. She’s not one to say, “Oh, I don’t think we can do this.” She looked at it and her eyes said, Yeah, I think we can do this. She had a few practical suggestions, but basically, Yeah, we can do this. It’s a bit of a challenge to be very far away from the conductor, especially when it’s not just 4/4 time all the way or waltz rhythm; there are lots of shifts of meter. But these are good players, these are pros.

LL: You can see, though, it is a a huge space, and it’s Diane Wittry’s job have to hold it all together! I met with her and showed her the score. She is great and she loves a challenge. She’s not one to say, “Oh, I don’t think we can do this.” She looked at it and her eyes said, Yeah, I think we can do this. She had a few practical suggestions, but basically, Yeah, we can do this. It’s a bit of a challenge to be very far away from the conductor, especially when it’s not just 4/4 time all the way or waltz rhythm; there are lots of shifts of meter. But these are good players, these are pros. IA: It’s like you have made a piece of visual and architectural art as well as sound-art.

IA: It’s like you have made a piece of visual and architectural art as well as sound-art. LL: That’s the idea. There’s really no reason the orchestra has to just sit on the stage. I don’t want the placement to be just a gimmick; it’s an integral part of what the piece is all about.

LL: That’s the idea. There’s really no reason the orchestra has to just sit on the stage. I don’t want the placement to be just a gimmick; it’s an integral part of what the piece is all about. IA: Now, one of your very recent projects with the Baltimore Consort was a recording of Spanish Renaissance music. Do you think any of those rhythms or sounds are in your ear?

IA: Now, one of your very recent projects with the Baltimore Consort was a recording of Spanish Renaissance music. Do you think any of those rhythms or sounds are in your ear? LL: That’s interesting that you mention that, because I started out listening to those pieces again. At one point I was considering writing a set of variations on one of those tunes. But I just rejected that; I got a little bit into it and thought: This isn’t what I want to do; it doesn’t sound like a fanfare. There’s really nothing on that CD that sounds like a fanfare. So I listened to Carmen again and got this idea and realized this is what I want to do. But I love the Spanish music of the Renaissance. It was a very interesting time period; 1492, when worlds were coming apart and together and Columbus was traveling here but there were clashes between the Christians and the Muslims, the Jews were expelled then the Muslims were expelled. Three different influences in the music. A very exiting time. We still perform that program quite a bit. but I just thought it wouldn’t really fit to bring that music into this.

LL: That’s interesting that you mention that, because I started out listening to those pieces again. At one point I was considering writing a set of variations on one of those tunes. But I just rejected that; I got a little bit into it and thought: This isn’t what I want to do; it doesn’t sound like a fanfare. There’s really nothing on that CD that sounds like a fanfare. So I listened to Carmen again and got this idea and realized this is what I want to do. But I love the Spanish music of the Renaissance. It was a very interesting time period; 1492, when worlds were coming apart and together and Columbus was traveling here but there were clashes between the Christians and the Muslims, the Jews were expelled then the Muslims were expelled. Three different influences in the music. A very exiting time. We still perform that program quite a bit. but I just thought it wouldn’t really fit to bring that music into this. IA: Now, do any of your other experiences tie into this fanfare? You have done at least one film score and at least one score for a play. Those are both theatrical.

IA: Now, do any of your other experiences tie into this fanfare? You have done at least one film score and at least one score for a play. Those are both theatrical. LL: Yes. I do like to write about extra-musical ideas: dramatic ideas or poetic ideas. When I wrote my concertos, I had characters from the Commedia dell’arte tradition, so they are named after characters: Pierrot, Harlequin, and Scaramouche. I had little scenarios in mind. Nothing very specific, but that helped me to imagine the characters musically.

LL: Yes. I do like to write about extra-musical ideas: dramatic ideas or poetic ideas. When I wrote my concertos, I had characters from the Commedia dell’arte tradition, so they are named after characters: Pierrot, Harlequin, and Scaramouche. I had little scenarios in mind. Nothing very specific, but that helped me to imagine the characters musically. IA: Can you talk about the film score you wrote for The Juniper Tree?

IA: Can you talk about the film score you wrote for The Juniper Tree? LL: Well, that happened a long time ago. That was, oh maybe 20 years ago or so.

LL: Well, that happened a long time ago. That was, oh maybe 20 years ago or so. IA: I think the film came out in 1990.

IA: I think the film came out in 1990. LL: That could be right. I was friendly with a filmmaker at UCLA. I forget how we met, or maybe I was recommended to her by somebody, but she contacted me and said she was working on a film based on the Grim fairytale The Juniper Tree. It was filmed in Iceland, in black-and-white; she wanted it to be very Medieval-looking, very austere. She asked if I could write music that would fit that mood.

LL: That could be right. I was friendly with a filmmaker at UCLA. I forget how we met, or maybe I was recommended to her by somebody, but she contacted me and said she was working on a film based on the Grim fairytale The Juniper Tree. It was filmed in Iceland, in black-and-white; she wanted it to be very Medieval-looking, very austere. She asked if I could write music that would fit that mood. IA: I saw the trailer, and it certainly achieved that look and that sound.

IA: I saw the trailer, and it certainly achieved that look and that sound.Note: you can login to watch the full movie here

LL: And the interesting thing is that it has become kind of a cult film because of Björk. Without Björk no one would have ever noticed it.

LL: And the interesting thing is that it has become kind of a cult film because of Björk. Without Björk no one would have ever noticed it. IA: It was her debut, right?

IA: It was her debut, right? LL: It was her debut. She looked like a 12-year-old, she’s supposed to be the younger sister, and she looked very young. But in fact she was maybe 20, and was pregnant, which they had to kind of cover up with loose clothing. But she was good! The film has some currency because of that. It was fun. What I did is I researched some Icelandic music because I wanted to see what some folk traditions were. It deals with folk elements, obviously, about people in the country trying to survive in a very harsh landscape. I kept the music very simple and I used instruments that I thought might approximate the folk instruments of early Northern Europe. I wanted the singing to be very simple. But some of the language, the vocabulary, was quite dissonant. It is a story of today as well as of the past, so I didn’t just want to recreate the music. I have some eerie effects with voices. There are some very compelling moments visually, so I wanted to capture those. I do enjoying watching films with an eye towards how the music is supporting the action. There are films in which I find that the music is irritatingly present, or underlines the action unnecessarily, or becomes a nuisance or an annoyance. I think film music should be in the support of the action.

LL: It was her debut. She looked like a 12-year-old, she’s supposed to be the younger sister, and she looked very young. But in fact she was maybe 20, and was pregnant, which they had to kind of cover up with loose clothing. But she was good! The film has some currency because of that. It was fun. What I did is I researched some Icelandic music because I wanted to see what some folk traditions were. It deals with folk elements, obviously, about people in the country trying to survive in a very harsh landscape. I kept the music very simple and I used instruments that I thought might approximate the folk instruments of early Northern Europe. I wanted the singing to be very simple. But some of the language, the vocabulary, was quite dissonant. It is a story of today as well as of the past, so I didn’t just want to recreate the music. I have some eerie effects with voices. There are some very compelling moments visually, so I wanted to capture those. I do enjoying watching films with an eye towards how the music is supporting the action. There are films in which I find that the music is irritatingly present, or underlines the action unnecessarily, or becomes a nuisance or an annoyance. I think film music should be in the support of the action. IA: Who are some current film composers whose work you admire?

IA: Who are some current film composers whose work you admire? LL: Oh, I like some of the big names: Hans Zimmer, Howard Shore, occasionally Jamie Horner. Sometimes they are a little over the top. I like Patrick Doyle. A lot of my students, actually, are interested in writing music for film—or now, more currently, video game music. That is timely, increasingly they are more interested in that because it is culturally relevant for them.

LL: Oh, I like some of the big names: Hans Zimmer, Howard Shore, occasionally Jamie Horner. Sometimes they are a little over the top. I like Patrick Doyle. A lot of my students, actually, are interested in writing music for film—or now, more currently, video game music. That is timely, increasingly they are more interested in that because it is culturally relevant for them. IA: Where is that music going right now? Is it still in that big German Romantic harmonic tradition?

IA: Where is that music going right now? Is it still in that big German Romantic harmonic tradition? LL: A lot of Japanese composers are taking the lead there, and they have come out of a tradition that often has very lush, rich, Romantic-sounding music. But it also has some “Eastern” sensibilities about it. Sometimes the music has to be modular, so you can’t really have music that grows organically in film music the way you could with symphonic music. People don’t have the patience for that anymore. They want quick, small pieces, rather than just sitting and listening to [the first four notes of Beethoven’s Fifth] evolve over time, how a composer develops an idea. That’s more of a nineteenth century, early twentieth-century idea. I think sometimes our minds are just now geared towards getting something quick and self-contained, rather than allowing ourselves the luxury of a symphony. I think music has evolved that way whether we know it or not. I’m not sure it’s a good thing, necessarily.

LL: A lot of Japanese composers are taking the lead there, and they have come out of a tradition that often has very lush, rich, Romantic-sounding music. But it also has some “Eastern” sensibilities about it. Sometimes the music has to be modular, so you can’t really have music that grows organically in film music the way you could with symphonic music. People don’t have the patience for that anymore. They want quick, small pieces, rather than just sitting and listening to [the first four notes of Beethoven’s Fifth] evolve over time, how a composer develops an idea. That’s more of a nineteenth century, early twentieth-century idea. I think sometimes our minds are just now geared towards getting something quick and self-contained, rather than allowing ourselves the luxury of a symphony. I think music has evolved that way whether we know it or not. I’m not sure it’s a good thing, necessarily. IA: Do you have to adapt to that or take it into account?

IA: Do you have to adapt to that or take it into account? LL: I do take it into account. I sometimes find in my own writing I gravitate that way, too, maybe because I gravitate that way or I’m thinking that my audience is that way, too. A little while ago I gave a talk about how Google, or the whole idea of the Internet, has changed our way of thinking. And while it’s a wonderful vehicle for getting information, it’s not always a wonderful vehicle for doing deep and contemplative thinking about something. It’s not to say that you can’t; Google is just a tool. It should allow us to go very deep into something, because it opens up a world of articles and books much more quickly. Part of tt is that we get impatient and we want to move around very quickly, so we don’t take the time to absorb something. It’s so attractive to click on links, and get little bits of information here, link, link, link. We don’t necessarily stay with anything for a long time. It’s interesting how technology can change how we think and how we write and how we listen to and take in art.

LL: I do take it into account. I sometimes find in my own writing I gravitate that way, too, maybe because I gravitate that way or I’m thinking that my audience is that way, too. A little while ago I gave a talk about how Google, or the whole idea of the Internet, has changed our way of thinking. And while it’s a wonderful vehicle for getting information, it’s not always a wonderful vehicle for doing deep and contemplative thinking about something. It’s not to say that you can’t; Google is just a tool. It should allow us to go very deep into something, because it opens up a world of articles and books much more quickly. Part of tt is that we get impatient and we want to move around very quickly, so we don’t take the time to absorb something. It’s so attractive to click on links, and get little bits of information here, link, link, link. We don’t necessarily stay with anything for a long time. It’s interesting how technology can change how we think and how we write and how we listen to and take in art. IA: How does that affect you if you sit down to write a large-scale piece, say, a symphony or a concerto?

IA: How does that affect you if you sit down to write a large-scale piece, say, a symphony or a concerto? LL: Well, I haven’t written a large-scale piece in a while. I did write a flute concerto a couple of years ago, that the Lehigh Valley Chamber Orchestra did. That was in four movements; each was about maybe five or six minutes long. and maybe the largest scale single-movement piece I have done, maybe 12 years ago, was 15- or 16-minute piece that stood by itself. But not the pieces are broken into shorter movements. It’s typical even back in Mozart’s day, if you wrote a symphony, it tended to be into shorter movements. You get into the nineteenth century and a symphony by Mahler: a movement can be thirty or forty minutes! A symphony can be a hour and a half! But we’re not in that culture anymore. The idea is that we need to get the message out more quickly. Television has changed the way we perceive things, the way we go from one quick cut to another quick cut. I had a friend who thought a good model for writing a piece was a one-minute commercial. The typical commercial was a series of images: if it’s about headache medication, we see this sufferer, then we see a remedy, then we return to the sufferer now that he or she has taken this medication. Now that has a certain form.

LL: Well, I haven’t written a large-scale piece in a while. I did write a flute concerto a couple of years ago, that the Lehigh Valley Chamber Orchestra did. That was in four movements; each was about maybe five or six minutes long. and maybe the largest scale single-movement piece I have done, maybe 12 years ago, was 15- or 16-minute piece that stood by itself. But not the pieces are broken into shorter movements. It’s typical even back in Mozart’s day, if you wrote a symphony, it tended to be into shorter movements. You get into the nineteenth century and a symphony by Mahler: a movement can be thirty or forty minutes! A symphony can be a hour and a half! But we’re not in that culture anymore. The idea is that we need to get the message out more quickly. Television has changed the way we perceive things, the way we go from one quick cut to another quick cut. I had a friend who thought a good model for writing a piece was a one-minute commercial. The typical commercial was a series of images: if it’s about headache medication, we see this sufferer, then we see a remedy, then we return to the sufferer now that he or she has taken this medication. Now that has a certain form. IA: Theme, development, restatement.

IA: Theme, development, restatement. LL: Right: ABA form. I am interested in how we shape something in a short amount of time. One thing that I have spent a lot of time thinking about and talking about with my students is Rhetoric. This is a subject that goes all the way back to the ancient Greeks, as part of the Trivium and Quadrivium of Medieval institutes.You used to be able to take classes in Rhetoric. Some schools still offer it; now it’s often just called Communication. But it is a way of organizing your thinking and your speaking. Rhetoric is part of persuasive speech. I’m always interested in the relationship between language and music and how the way one might organize a speech might be the way one might organize a piece of music. For example, let’s say a lawyer is arguing a case, or a speaker is speaking before the Senate. He would have an introduction, and then sort of lay out the facts, and then there is a section in rhetoric where you have alternate facts, or secondary facts; you discuss: Well, what if that didn’t happen? or: This is an alternative to that. And then you come back and repeat the facts again, summarize everything, and then have your conclusion. It’s a pretty good analogy to what we call Sonata Form in music. You have your introduction, you have not a laying-out of facts, but a laying-out of a theme. You have a second theme, which is different. It doesn’t refute the second theme, it just presents a contrast. And then you mix it up together. And then you restate that first theme. And then you sort of summarize that, in what musicians call the Recapitulation. And then you have your Coda, which is your summary to the jury. It does kind of follow that form.

LL: Right: ABA form. I am interested in how we shape something in a short amount of time. One thing that I have spent a lot of time thinking about and talking about with my students is Rhetoric. This is a subject that goes all the way back to the ancient Greeks, as part of the Trivium and Quadrivium of Medieval institutes.You used to be able to take classes in Rhetoric. Some schools still offer it; now it’s often just called Communication. But it is a way of organizing your thinking and your speaking. Rhetoric is part of persuasive speech. I’m always interested in the relationship between language and music and how the way one might organize a speech might be the way one might organize a piece of music. For example, let’s say a lawyer is arguing a case, or a speaker is speaking before the Senate. He would have an introduction, and then sort of lay out the facts, and then there is a section in rhetoric where you have alternate facts, or secondary facts; you discuss: Well, what if that didn’t happen? or: This is an alternative to that. And then you come back and repeat the facts again, summarize everything, and then have your conclusion. It’s a pretty good analogy to what we call Sonata Form in music. You have your introduction, you have not a laying-out of facts, but a laying-out of a theme. You have a second theme, which is different. It doesn’t refute the second theme, it just presents a contrast. And then you mix it up together. And then you restate that first theme. And then you sort of summarize that, in what musicians call the Recapitulation. And then you have your Coda, which is your summary to the jury. It does kind of follow that form.That’s on one level. And then on another level we have what you might call rhetorical devices. Like metaphor, simile… And there are musical analogies to some of these rhetorical devices. Not necessarily metaphor and simile, but one that is interesting is a rhetorical device called the anaphora, which is a repetition, usually a rather strong repetition, at the beginning of a phrase, so that the repetition kind of hammers the point out. When Hilary Clinton was talking about what it takes to raise a child: “It takes dedication, it takes a community, it takes, it takes….” She’s saying “It takes” at the beginning of each. That’s anaphora. If you have a politician who says: “The people demand change! The people are fed up with higher taxes! The people want…” you know, all that stuff. So that’s a rhetorical device. A composer can do that, too. And composers have done that. They repeat things in a dramatic way. I’m aware of that. I have my students practice writing anaphoristic phrases just to see what it’s like to do that. That’s just one example. Then there’s the climax, the peak, of a piece of music. In rhetoric it’s not so much the peak itself, it’s how you get there, it’s the process. And so we look at this very famous speech by a theologian named Richard Hooker. He has sentence that is like 186 words long, and it just starts very quietly, and then the images get more graphic, and the phrases get shorter. It builds to a beautiful climax and you finally get his point. You’re kind of swept along by his verbiage. If you just went straight to his point it wouldn’t be nearly as dramatic. It kind of takes us there…. So I have my students write a phrase, or it might be something equivalent to that, and build through a crescendo. A crescendo is one way to create a climax, but there are other ways, too.

IA: Layered instrumentation…

IA: Layered instrumentation… LL: Exactly! Layered instrumentation, rhythmic complexity, harmonic complexity. All these things the composer has.

LL: Exactly! Layered instrumentation, rhythmic complexity, harmonic complexity. All these things the composer has. IA: Delaying a harmonic resolution…

IA: Delaying a harmonic resolution… LL: Absolutely. All these things. It’s kind of fun to train them that these are time-tested ways that people have communicated, so we as composers can communicate that way, too.

LL: Absolutely. All these things. It’s kind of fun to train them that these are time-tested ways that people have communicated, so we as composers can communicate that way, too. IA: Wow. I’m going to take this to my College English One class and tell them: your five-paragraph essay? That’s a Sonata Form!

IA: Wow. I’m going to take this to my College English One class and tell them: your five-paragraph essay? That’s a Sonata Form! LL: There you go. There are all sorts of rhetorical devices that have musical analogies.

LL: There you go. There are all sorts of rhetorical devices that have musical analogies. IA: Let’s talk a little bit more about your musical vocabulary, and maybe just a really brief history of what was your relationship, say, with serialism, what was your relationship, say, with minimalism, and then who you are now and whether you would describe yourself in terms of a particular school of composition.

IA: Let’s talk a little bit more about your musical vocabulary, and maybe just a really brief history of what was your relationship, say, with serialism, what was your relationship, say, with minimalism, and then who you are now and whether you would describe yourself in terms of a particular school of composition. LL: Yes. Well, I guess like everyone you sort of start off writing the kind of music you are comfortable with, that you’re listening to a lot. So early on I would write imitation of other styles in tonal music. And then you’re introduced to new concepts at school. I had to write some serial pieces. For a while I wrote what you might call “friendly” atonal music, because I didn’t always use a key center, a pitch center, but I liked there to be relationships. It might be triadic without actual being tonal. I also liked the sound of triads, but I would not always necessarily have a key for them to resolve in. Much of my music had that quality. I never really was taken with trying to write minimal music myself. I enjoy listening to some of it, and I teach it, and I am interested in how that as a style has evolved from the early days of the 60s to what might be called now, or at least what those composers who were early minimalists are doing now. I didn’t ever see myself as someone who did that. I guess I grew up in the tradition where you had an idea and you developed it and nurtured that idea: sort of the old-school way that I was taught, and so I keep doing that. I would say, over time, my music has maybe gotten a little more tonal, a little more key centered. You know, I really believe in communicating with my players and with my audience, too. I feel I have to be true to three constituencies: myself, my audience, and my performers. I want everyone to have a good experience. I have sometimes made the mistake of writing pieces that I thought intellectually made sense, but they were either too challenging for one reason or another, or didn’t come off in performance, and alienated the performers as well as the audience, so I thought: Well, that didn’t work! But then you grow from that. You learn why that didn’t work and what you could do differently next time. I still always like to do something different, something I’ve never done before. I don’t really ever like to repeat something that’s safe, because you don’t really grow as a performer. I admire the composers who are taking challenges and moving into new directions.

LL: Yes. Well, I guess like everyone you sort of start off writing the kind of music you are comfortable with, that you’re listening to a lot. So early on I would write imitation of other styles in tonal music. And then you’re introduced to new concepts at school. I had to write some serial pieces. For a while I wrote what you might call “friendly” atonal music, because I didn’t always use a key center, a pitch center, but I liked there to be relationships. It might be triadic without actual being tonal. I also liked the sound of triads, but I would not always necessarily have a key for them to resolve in. Much of my music had that quality. I never really was taken with trying to write minimal music myself. I enjoy listening to some of it, and I teach it, and I am interested in how that as a style has evolved from the early days of the 60s to what might be called now, or at least what those composers who were early minimalists are doing now. I didn’t ever see myself as someone who did that. I guess I grew up in the tradition where you had an idea and you developed it and nurtured that idea: sort of the old-school way that I was taught, and so I keep doing that. I would say, over time, my music has maybe gotten a little more tonal, a little more key centered. You know, I really believe in communicating with my players and with my audience, too. I feel I have to be true to three constituencies: myself, my audience, and my performers. I want everyone to have a good experience. I have sometimes made the mistake of writing pieces that I thought intellectually made sense, but they were either too challenging for one reason or another, or didn’t come off in performance, and alienated the performers as well as the audience, so I thought: Well, that didn’t work! But then you grow from that. You learn why that didn’t work and what you could do differently next time. I still always like to do something different, something I’ve never done before. I don’t really ever like to repeat something that’s safe, because you don’t really grow as a performer. I admire the composers who are taking challenges and moving into new directions.One characteristic of my music has been that I tend to change meters frequently. Conductors who know about that brace themselves when a piece of mine is coming. They think, OMG, maybe it will stay in one meter for more than ten seconds! 5/8, 7/8, ¾, 10/16, 7/8. I have done that. I confess. It’s not because I’m ADD or I just want to annoy people! It’s just how I feel the music should go. I try to put the music into meters that make sense to me and to the players. But it is a characteristic of a lot of my music.

IA: Do you think that your story is a microcosm for your generation of composers who were required to write in serialism and then lived through minimalism, maybe coming back to tonalism now?

IA: Do you think that your story is a microcosm for your generation of composers who were required to write in serialism and then lived through minimalism, maybe coming back to tonalism now? LL: It could be. Well, minimalism was always sort of a tonal reaction to complexity, a sort of stripping down of all the chromaticism and the rhythmic complexity and saying let’s go back to something simpler and repetitive. And some of the composers went that way without being minimal. They just said, I’m tied of serialism; I’m tired of mathematical relationships. So that definitely has been happening in my generation. They learned something, wrote that way, and then worked their way out of it. I don’t see any people who are sort of moving into serialism except if they’re just on a particular path of exploration and they want to do it. It doesn’t really have an audience, honestly. There are not a lot of people outside of academia who are interested in hearing atonal music.

LL: It could be. Well, minimalism was always sort of a tonal reaction to complexity, a sort of stripping down of all the chromaticism and the rhythmic complexity and saying let’s go back to something simpler and repetitive. And some of the composers went that way without being minimal. They just said, I’m tied of serialism; I’m tired of mathematical relationships. So that definitely has been happening in my generation. They learned something, wrote that way, and then worked their way out of it. I don’t see any people who are sort of moving into serialism except if they’re just on a particular path of exploration and they want to do it. It doesn’t really have an audience, honestly. There are not a lot of people outside of academia who are interested in hearing atonal music. IA: We’re still not whistling twelve-tone rows in the streets, and we never will!

IA: We’re still not whistling twelve-tone rows in the streets, and we never will! LL: We’re not, we’re not, and I don’t think we will! I can admire a composer like Elliott Carter who can write very complex music, but a lot of his music is very off-putting because it’s so dense, so chromatic, and so difficult that while it gets lots of awards, it has no appreciable audience.

LL: We’re not, we’re not, and I don’t think we will! I can admire a composer like Elliott Carter who can write very complex music, but a lot of his music is very off-putting because it’s so dense, so chromatic, and so difficult that while it gets lots of awards, it has no appreciable audience. IA: What are some of your strongest composition students, current students or recent graduates, working in?

IA: What are some of your strongest composition students, current students or recent graduates, working in? LL: I have some who are interested in film. One student went to North Carolina School of the Arts just to work more in film music. He wrote a nice piece that the orchestra did here last year. I don’t think ,any of them will be professional composers; some of them have gone on to teach. Most of my students here are music education students who take composition, but I have three or four actual composition majors. And it’s hard to know what’s going to happen with them. There is not a huge market for contemporary music, so you have to figure out what are you going to do with this. And sometimes they are natural teachers and they teach. Others might go on to something else. Often there’s a bond between technology or computer work and composition, so often they gravitate in that direction and do some composing, too.

LL: I have some who are interested in film. One student went to North Carolina School of the Arts just to work more in film music. He wrote a nice piece that the orchestra did here last year. I don’t think ,any of them will be professional composers; some of them have gone on to teach. Most of my students here are music education students who take composition, but I have three or four actual composition majors. And it’s hard to know what’s going to happen with them. There is not a huge market for contemporary music, so you have to figure out what are you going to do with this. And sometimes they are natural teachers and they teach. Others might go on to something else. Often there’s a bond between technology or computer work and composition, so often they gravitate in that direction and do some composing, too. IA: Do you think that the world of contemporary classical music needs a huge new breakthrough? Needs a huge idea like the Second Viennese School?

IA: Do you think that the world of contemporary classical music needs a huge new breakthrough? Needs a huge idea like the Second Viennese School? LL: It’s hard to know. Two years ago, we took the music department to see John Adams’ opera Dr. Atomic. I was very curious, because I wanted to see what John Adams was doing right now. And yet, what is it? It’s quite tonal, quite lyrical; there are some real singable arias. One of the students said, “I want to do that song in my recital!” That hardly ever happens when you go to a contemporary work. It is hard to generalize, but the successful composers are the ones who are getting commissions to write pieces that do reach out and don’t put up barriers but are trying to be communicative. Stephen Paulus is someone who writes very well, and his music is tonal, for the most part.

LL: It’s hard to know. Two years ago, we took the music department to see John Adams’ opera Dr. Atomic. I was very curious, because I wanted to see what John Adams was doing right now. And yet, what is it? It’s quite tonal, quite lyrical; there are some real singable arias. One of the students said, “I want to do that song in my recital!” That hardly ever happens when you go to a contemporary work. It is hard to generalize, but the successful composers are the ones who are getting commissions to write pieces that do reach out and don’t put up barriers but are trying to be communicative. Stephen Paulus is someone who writes very well, and his music is tonal, for the most part.We don’t see too much absolute music anymore. It tends to be programmatic, or operas…. I think people are still writing operas and there are still commissions for operas. I’m always amazed that opera has stood the test of time from the Baroque period. It’s such an extravagant art form and ridiculous in some ways! But so compelling. People who write operas keeping writing them, because there’s a real lure. I wrote one opera, and it was so much work, and it was fun, but I wonder if I would have the energy to do that again. Mozart would write an opera and then he just kept wanting to write them, even though he was writing tons of other stuff too. If you have that gift of drama and story-telling and you like language and you like dance and everything else and you like the whole to be part of something larger, it’s really addictive. You can see why he kept doing it, but you can also see why he died when he did! It killed him to do all that!

Paul Salerni, one of the fanfare composers, writes operas. I really respect Paul very much. Well, I don’t want to tell his story for him, but he’s, you know, he went to Harvard, studied with Earl Kim. He got that very rigorous education there, but his music is very tonal. There’s a jazz influence at times, a pop influence in other ways. His first opera, Tony Caruso’s Final Broadcast, he said it’s almost musical theater. There are those elements. It’s part of the story: there are jazz elements, pop elements, deliberately so, and other parts that are not. I got to know it fairly well, because Rory, my son, was playing a role. Its beautiful writing! It’s really, really gorgeous. Paul has that advantage Italians have somehow. They have that beautiful language, and Italian composers from Monteverdi on have great, lyrical writing. They’re always, down through the line, Verdi, Puccini, even Luciano Berio, who might be the leading Italian composer of the twentieth century, still can write very interestingly for voice. They just feel at home. I’m looking forward to his next opera, The Life and Love of Joe Coogan. It is light, and I think that’s a direction Paul has gone. Some of his other music tends to be story-telling and light. He’s no longer interested in pushing an envelope towards wherever he might have been pushing twenty years ago, and I’m not either.

IA: He said something very similar: No matter what it is, no matter what the vocabulary of it is, it’s always about communicating something, it’s about telling a story.

IA: He said something very similar: No matter what it is, no matter what the vocabulary of it is, it’s always about communicating something, it’s about telling a story. LL: Absolutely. Steven Stametz is another composer who does that, too. Beautiful writing.

LL: Absolutely. Steven Stametz is another composer who does that, too. Beautiful writing. IA: Are there any other future predictions or current observations you want to make?

IA: Are there any other future predictions or current observations you want to make? LL: Well, I’m always interested to see how technology always moves at such a fast pace. It can be exhausting to keep up with it, and sometimes I find myself annoyed that sometimes the technology is the tail that wags the dog, and some people are overly reliant on it, or they think that technology replaces actual composition. Just the way a filmmaker might use technology to make a visually stunning movie, but without any substance. I have actually seen movies like that. So it’s never going to replace our critical thinking. Sometimes it’s a distraction. Being at a liberal arts college where they drill you, hammer you, about the need for critical thinking is still very important. I always like to wave that particular flag.

LL: Well, I’m always interested to see how technology always moves at such a fast pace. It can be exhausting to keep up with it, and sometimes I find myself annoyed that sometimes the technology is the tail that wags the dog, and some people are overly reliant on it, or they think that technology replaces actual composition. Just the way a filmmaker might use technology to make a visually stunning movie, but without any substance. I have actually seen movies like that. So it’s never going to replace our critical thinking. Sometimes it’s a distraction. Being at a liberal arts college where they drill you, hammer you, about the need for critical thinking is still very important. I always like to wave that particular flag.

No comments:

Post a Comment