Though each day may be dull or stormy, works of art are islands of joy. Nature and poetry evoke "Sehnsucht," that longing for Heaven C.S. Lewis described. Here we spend a few minutes enjoying those islands, those moments in the sun.

19 September 2006

Unfinished Tolkien work to be published

This is interesting news: J.R.R. Tolkien's son Christopher has finished a book his father began but never completed, The Children of Hurin. It will be published in 2007. Given that the younger Tolkien has been working on this for the past 30 years, I wonder how much of the work is his father's and how much is his. Nevertheless, fans of Middle Earth will surely go nuts over another story about the elves and dwarves from LOTR. CNN story.

13 September 2006

Macbeth and Predestination

Read: C. S. Lewis: A Biography by Roger Lancelyn Green & Walter Hooper.

Watched: the first part of HBO’s Elizabeth I

This is a re-hash of a previous post. My students & I have been exploring this topic in Language Arts classes recently, so I repost it here for their sakes, looking forward to their comments.

David Taylor once said artists must read their systematic theology. Indeed, I do believe that great Christian art is (partly) only as good as its doctrine. Partly; skill/craftsmanship/aesthetic excellence are also essential. But I also think that the debates over theological points are as fertile as solid convictions. The “Problem of Evil,” for example, functions as the catalyst for large passages in Augustine’s Confessions, Dante’s trilogy, Milton’s Paradise Lost….

And the debate over Free Will vs. Predestination is another such matter. We’ve been reading Macbeth for the last month or more, putting it into the context of cultural controversies. One hot topic of Shakespeare’s time was this problem about “Does God deterimine all things beofre they begin, or are human beings free to create their own [eternal] destinies?” And it was very hot; wars were raging all over Europe in the latter half of the 16th century over Catholicism, Anglicanism, Lutheranism, and Calvinism. Shakespeare, man of the age, was certainly not going to let this red-letter debate slip by. But he also didn’t want to lose his head.

However that may be, the author of the introductory matter in our Norton Critical Edition, Robert S. Miola, claims that “Whatever his personal convictions, Shakespeare clearly adopts a Catholic view of the action and theology of free will in this play” and “the doctrine of predestination renders human action essentially undramatic: when the end is known, preordained, and absolutely just, there can be no real choice, suspense, conflict, or resolution. This conception of divine justice and human action renders pity an impertinence, terror a transgression, and tragedy an impossibility” (pp. xv, xvi).

Maybe we shouldn’t be so sure. I have a problem with that sweeping generalization. I wouldn’t say that predestination freezes all possibility of dramatic action. I’d like to make two points:

1. The characters do not know the ending. They are within a double predestination, as it were. Theologians will pardon me for abusing the term. First, they might be predestined by God, if such is the writer’s or audience’s belief. Second, they are certainly predestined by the intent and will of the artist. Or perhaps I have those in the wrong order?

2. In life, we do not know our ending. The staunchest Calvinist, if he has his wits about him, believes that here inside time we must make choices. Yeah, perhaps God has set the choice before hand, certainly God knows what will be done, but that does not make the psychological and emotional experience of choice any less a reality. Any less real. It is also thus inside works of art.

So, here’s the question: Is Macbeth free to choose his fate, or is he destined to follow the prophecies? We’ve talked about how much the witches knew, could they see the future, would Macbeth have become king even without killing Duncan, are the “equivocating” words of the weird sisters quite “fair” from a spiritual point of view, do telling the future and making big decisions create parallel universes… you know, the usual literary discussions. :)

So now, let’s continue that conversation. Feel free to answer the above question, offer new questions, or give other examples of how this doctrinal dilemma has been the catalyst for great passages of writing. Or I’d really love to see examples of other genres (visual arts, music, etc.) that use this or other theological paradoxes for their meaning and motive!

Watched: the first part of HBO’s Elizabeth I

This is a re-hash of a previous post. My students & I have been exploring this topic in Language Arts classes recently, so I repost it here for their sakes, looking forward to their comments.

David Taylor once said artists must read their systematic theology. Indeed, I do believe that great Christian art is (partly) only as good as its doctrine. Partly; skill/craftsmanship/aesthetic excellence are also essential. But I also think that the debates over theological points are as fertile as solid convictions. The “Problem of Evil,” for example, functions as the catalyst for large passages in Augustine’s Confessions, Dante’s trilogy, Milton’s Paradise Lost….

And the debate over Free Will vs. Predestination is another such matter. We’ve been reading Macbeth for the last month or more, putting it into the context of cultural controversies. One hot topic of Shakespeare’s time was this problem about “Does God deterimine all things beofre they begin, or are human beings free to create their own [eternal] destinies?” And it was very hot; wars were raging all over Europe in the latter half of the 16th century over Catholicism, Anglicanism, Lutheranism, and Calvinism. Shakespeare, man of the age, was certainly not going to let this red-letter debate slip by. But he also didn’t want to lose his head.

However that may be, the author of the introductory matter in our Norton Critical Edition, Robert S. Miola, claims that “Whatever his personal convictions, Shakespeare clearly adopts a Catholic view of the action and theology of free will in this play” and “the doctrine of predestination renders human action essentially undramatic: when the end is known, preordained, and absolutely just, there can be no real choice, suspense, conflict, or resolution. This conception of divine justice and human action renders pity an impertinence, terror a transgression, and tragedy an impossibility” (pp. xv, xvi).

Maybe we shouldn’t be so sure. I have a problem with that sweeping generalization. I wouldn’t say that predestination freezes all possibility of dramatic action. I’d like to make two points:

1. The characters do not know the ending. They are within a double predestination, as it were. Theologians will pardon me for abusing the term. First, they might be predestined by God, if such is the writer’s or audience’s belief. Second, they are certainly predestined by the intent and will of the artist. Or perhaps I have those in the wrong order?

2. In life, we do not know our ending. The staunchest Calvinist, if he has his wits about him, believes that here inside time we must make choices. Yeah, perhaps God has set the choice before hand, certainly God knows what will be done, but that does not make the psychological and emotional experience of choice any less a reality. Any less real. It is also thus inside works of art.

So, here’s the question: Is Macbeth free to choose his fate, or is he destined to follow the prophecies? We’ve talked about how much the witches knew, could they see the future, would Macbeth have become king even without killing Duncan, are the “equivocating” words of the weird sisters quite “fair” from a spiritual point of view, do telling the future and making big decisions create parallel universes… you know, the usual literary discussions. :)

So now, let’s continue that conversation. Feel free to answer the above question, offer new questions, or give other examples of how this doctrinal dilemma has been the catalyst for great passages of writing. Or I’d really love to see examples of other genres (visual arts, music, etc.) that use this or other theological paradoxes for their meaning and motive!

10 September 2006

Resources on Christianity and the Arts

I sent an email this evening to a pastor friend of mine who had recently asked me for some suggested resources on Christianity and the Arts. It's worth reproducing here, with some minor tweaks and book links added.

Books/Articles:

Rookmaaker, Hans. Modern Art and the Death of a Culture. A bit dated, but still a classic in this field. Rookmaaker, along with Francis Schaeffer, was one of the early influences on evangelicals finally coming back to think seriously about the arts.

Sayers, Dorothy. The Mind of the Maker. She compares the human creative act (especially that of writing) to God's creative act and sees trinitarian implications there.

Sayers, Dorothy. The Zeal of thy House. Wonderful play about an architect who struggles with faith, defiance towards God, and pride. He designs a cathedral which ultimately serves as the act of worship he was unable to give any other way. "Behold, he prayeth; not with the lips alone, / But with the hand and with the cunning brain / Men worship the Eternal Architect. / So, when the mouth is dumb, the work shall speak / And save the workman." Out of print; limited availability/expensive in used market; check libraries.

Begbie, Jeremy. Voicing Creation's Praise: Towards a Theology of the Arts. Very scholarly/theoretical, but gives a good foundation. Begbie is a brilliant musician/theologian from the UK, one of the key names in the arena of faith and the arts today. I know him personally. He's taught summer school classes at Regent, and I supported and attended his "Theology Through the Arts" conference in Cambridge in 2000. Fabulous!

Begbie. Jeremy, ed. Beholding the Glory: Incarnation Through the Arts. A more readable collection of essays about theology through various specific arts: literature, poetry, dance, icons, sculpture, music.

Johnston, Robert. Reel Spirituality: Theology and Film in Dialogue. Encourages a two-way conversation between theology and film. The stories in films can teach us about reality, and a theological perspective can help us interpret films.

Wolterstorff, Nicholas. Art in Action: Toward a Christian Aesthetic. Sees art as an instrument of action in the world, and artists as responsible servants.

Van Gogh, Vincent. The Letters of Vincent van Gogh. Intriguing insight into the mind and spiritual life of an artist who was very tormented by his vocation, but who truly saw it as a calling from God, and in spite of his tragic life ended up making a huge impact with his art.

Wilkinson, Loren. "'Art as Creation' or 'Art as Work'?" Crux, March 1983, pp. 23-28. I can't improve on Brad Baurain's summary: "An excellent essay, seeking a synthesis between sacramentalist (emphasizing creativity) and Reformed (emphasizing stewardship) perspectives on the arts." Loren is a friend of mine and one of my favorite professors at Regent. Alas, the article is not available online, but it should be, and I'm working on trying to rectify that (permissions, etc.)

Larsen, David. The Company of the Creative: A Christian Reader's Guide to Great Literature and Its Themes. A very useful reference book.

Debray, Régis. The Old Testament Through 100 Masterpieces of Art, and The New Testament Through 100 Masterpieces of Art. Two volumes of excellent reproductions of great art depicting themes in the Bible, with commentary.

Essays online:

Vonnahme, Nathan. "Art as Witness." Paper written for Regent College class "The Christian Imagination."

Websites:

Image Journal - the premier journal of Christian faith and the arts; to its credit it has in a short while (50 issues) become one of the top 10 literary journals of any sort in the United States; poetry, short fiction, essays, visual art on color plates; high quality publication; co-sponsors the annual Glen Workshop (Christian artists/writers conference) in Santa Fe.

Christians in the Visual Arts - organization that encourages, promotes, and fosters networking among Christian visual artists; holds annual summer workshops at Gordon College, and co-sponsors the Glen Workshop with Image Journal.

Mars Hill Audio - engaging in contemporary culture from the vantage point of Christian conviction; they publish an audio journal and have lots of interviews related to the arts; some free tracks are available as MP3 downloads (click "Listen for Free")

Diary of an Arts Pastor (excellent blog by David Taylor) - David is a Regent alum and currently arts pastor at Hope Chapel in Austin, TX, a very arts-focused church indeed. He's a thoughtful writer, and is working on a book (to be published by Baker) on Christianity and the arts which promises to be very comprehensive (he's been posting outlines of his chapters as he works on it).

Iambic Admonit - this blog! :-)

Modern and Contemporary Poets of Christian Faith - a substantial list put together by a professor of English Literature at Dallas Baptist University

Art Index (aka Art Concordance) - thematic and Scripture indexes of artwork, with links to online reproductions

Movie Index (aka Movie Concordance) - topical index of movies with biblical themes, with links to reviews and articles about each movie

Ransom Fellowship's "Movie Central" - reviews and resources for leading movie discussions that will develop discernment and deepen discipleship.

Arts & Faith (discussion forums)

The Arts & Faith Top 100 Spiritually Significant Films

Books/Articles:

Rookmaaker, Hans. Modern Art and the Death of a Culture. A bit dated, but still a classic in this field. Rookmaaker, along with Francis Schaeffer, was one of the early influences on evangelicals finally coming back to think seriously about the arts.

Sayers, Dorothy. The Mind of the Maker. She compares the human creative act (especially that of writing) to God's creative act and sees trinitarian implications there.

Sayers, Dorothy. The Zeal of thy House. Wonderful play about an architect who struggles with faith, defiance towards God, and pride. He designs a cathedral which ultimately serves as the act of worship he was unable to give any other way. "Behold, he prayeth; not with the lips alone, / But with the hand and with the cunning brain / Men worship the Eternal Architect. / So, when the mouth is dumb, the work shall speak / And save the workman." Out of print; limited availability/expensive in used market; check libraries.

Begbie, Jeremy. Voicing Creation's Praise: Towards a Theology of the Arts. Very scholarly/theoretical, but gives a good foundation. Begbie is a brilliant musician/theologian from the UK, one of the key names in the arena of faith and the arts today. I know him personally. He's taught summer school classes at Regent, and I supported and attended his "Theology Through the Arts" conference in Cambridge in 2000. Fabulous!

Begbie. Jeremy, ed. Beholding the Glory: Incarnation Through the Arts. A more readable collection of essays about theology through various specific arts: literature, poetry, dance, icons, sculpture, music.

Johnston, Robert. Reel Spirituality: Theology and Film in Dialogue. Encourages a two-way conversation between theology and film. The stories in films can teach us about reality, and a theological perspective can help us interpret films.

Wolterstorff, Nicholas. Art in Action: Toward a Christian Aesthetic. Sees art as an instrument of action in the world, and artists as responsible servants.

Van Gogh, Vincent. The Letters of Vincent van Gogh. Intriguing insight into the mind and spiritual life of an artist who was very tormented by his vocation, but who truly saw it as a calling from God, and in spite of his tragic life ended up making a huge impact with his art.

Wilkinson, Loren. "'Art as Creation' or 'Art as Work'?" Crux, March 1983, pp. 23-28. I can't improve on Brad Baurain's summary: "An excellent essay, seeking a synthesis between sacramentalist (emphasizing creativity) and Reformed (emphasizing stewardship) perspectives on the arts." Loren is a friend of mine and one of my favorite professors at Regent. Alas, the article is not available online, but it should be, and I'm working on trying to rectify that (permissions, etc.)

Larsen, David. The Company of the Creative: A Christian Reader's Guide to Great Literature and Its Themes. A very useful reference book.

Debray, Régis. The Old Testament Through 100 Masterpieces of Art, and The New Testament Through 100 Masterpieces of Art. Two volumes of excellent reproductions of great art depicting themes in the Bible, with commentary.

Essays online:

Vonnahme, Nathan. "Art as Witness." Paper written for Regent College class "The Christian Imagination."

Websites:

Image Journal - the premier journal of Christian faith and the arts; to its credit it has in a short while (50 issues) become one of the top 10 literary journals of any sort in the United States; poetry, short fiction, essays, visual art on color plates; high quality publication; co-sponsors the annual Glen Workshop (Christian artists/writers conference) in Santa Fe.

Christians in the Visual Arts - organization that encourages, promotes, and fosters networking among Christian visual artists; holds annual summer workshops at Gordon College, and co-sponsors the Glen Workshop with Image Journal.

Mars Hill Audio - engaging in contemporary culture from the vantage point of Christian conviction; they publish an audio journal and have lots of interviews related to the arts; some free tracks are available as MP3 downloads (click "Listen for Free")

Diary of an Arts Pastor (excellent blog by David Taylor) - David is a Regent alum and currently arts pastor at Hope Chapel in Austin, TX, a very arts-focused church indeed. He's a thoughtful writer, and is working on a book (to be published by Baker) on Christianity and the arts which promises to be very comprehensive (he's been posting outlines of his chapters as he works on it).

Iambic Admonit - this blog! :-)

Modern and Contemporary Poets of Christian Faith - a substantial list put together by a professor of English Literature at Dallas Baptist University

Art Index (aka Art Concordance) - thematic and Scripture indexes of artwork, with links to online reproductions

Movie Index (aka Movie Concordance) - topical index of movies with biblical themes, with links to reviews and articles about each movie

Ransom Fellowship's "Movie Central" - reviews and resources for leading movie discussions that will develop discernment and deepen discipleship.

Arts & Faith (discussion forums)

The Arts & Faith Top 100 Spiritually Significant Films

08 September 2006

Till We Have Faces part two

Read: Jack’s Life by Douglas Gresham. A very sweet, tender bio of C. S. Lewis, by his stepson.

Listened to: Vivaldi’s “Autumn,” favorite Bollywood songs, the soundtrack to “Apollo XIII.”

Watched: The Question of God: Sigmund Freud & C. S. Lewis debate God, love, sex, and the meaning of life and World Trade Center.

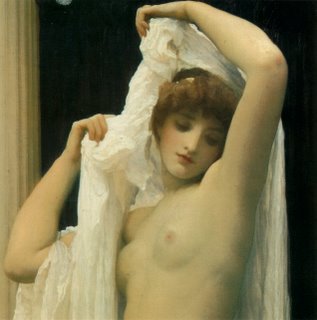

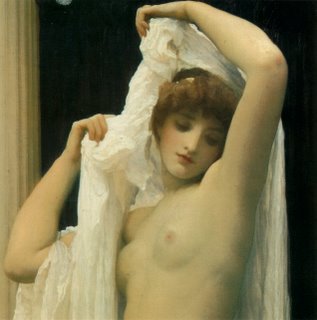

"Psyche" by Leighton

I said in my last post, “There are two main beauties of Till We Have Faces. One is the ‘big idea,’ Lewis’s mythopoeia,” and of this I intend to speak now. I called it previously “Christian Mythology,” and located it in Part II of this great book. What could I possibly mean by “Christian Mythology?” That sounds offensive to the Truth. But let me try to explain what CSL meant by it.

In Surprised by Joy, he writes that he had been taught, as a child, that Christianity was 100% true, and all other religions were 100% false. When he came to love the poetic beauty of the Norse myths (“Balder the beautiful is dead, is dead!”), he felt his soul moved in a way that none of his early Christian teaching had moved him. Also, during his theistic days, he felt his mind moving towards Christianity, but couldn’t understand the essence of it. Sinfulness, the need for redemption, that he got quite clearly. But he couldn’t, as he put it in a letter to Arthur Greeves, see how the life and death and resurrection of a man 2000 years ago had anything to do with spiritually rescuing people nowadays. Tolkien and Barfield came over to talk some sense—or supra-sense—into him. They reminded him that when he came across the idea of substitutionary sacrifice in a pagan myth, he was not only not offended by it, he loved it and was strangely moved, profoundly affected by something mysteriously and deeply true about it in a way that could not be translated into simple prose. The death and resurrection of, say, Gilgamesh, was beautiful and powerful in its mythological setting. Well, then, said Tolkien, Christ’s death and resurrection works the same way. It’s a sacrifice with all the emotional and psychological power of a myth, but with this enormous difference: it actually happened. The others didn’t happen in history, but they were God’s way of preparing the human soul and imagination to accept it when it did really happen. In other words, God put the concept of sacrifice deep into our spirits so that even pagan writers who do not believe in it feel its power and work it into their greatest poems/plays/etc.

This conversation with Tolkien & Barfield was enormously important to Lewis. A few days later (on 28 September 1931, to be exact) he came to believe that Jesus is indeed the Son of God. He finally knew how sacrifice works, and he knew it somewhere even deeper than in his intellect, in some place in his soul that didn't have to turn in into a mathimatical proof. In short, he was converted/justified/redeemed.

From then on, CSL e felt that the idea of Christianity as the "true myth" solved the terrible problem of comparative religions—it answered that awful question, “How can your religion be perfectly true and all others perfectly false when they have important bits in common?” It explained to him, in a huge and universal way, the principles of Natural Law (otherwise known as General Revelation) outlined in Romans chapter one. It set him at rest, that he could fully commit his intellect to Christianity and it would actually help him understand the cultural and literary significance of all the other religions and philosophies that stirred his poetic imagination and thrilled his heart.

So he created a perfect myth. Till We Have Faces is one of his last books and, I believe, his best. The very feeling and faith of the pagan religion of Glome is inherent to TWHF. The Cult of Ungit is at once a false religion (“It’s very strange that our fathers should first think it worth telling us that rain falls out of the sky, and then, for fear such a notable secret should get out… wrap it up in a filthy tale so that no one could understand the telling”) and yet reveals true spiritual principles. The poor woman who come with her offering finds calm and peace and comfort in praying to that shapeless mass of stone. The crowds greeting the priest are full of joy. Every poor man and woman in that pitiful kingdom longs for the divine, longs for the comfort and the beauty of the gods.

And Orual rejected it. She became Ungit; ugly in soul, unmendable. She came to “the very bottom”; her nakedness before the gods, the worst and best that could be true. This is the first necessary stage of conversion: abject remorse, bitter horror at one’s own worthlessness, the depth of one’s own sin. At the river, the god told her “Die before you die; there is no chance after.” She needed to be buried in baptism and rise again out of herself. She had turned away from Joy, from “the everlasting calling, calling, calling of the gods.”

But in the very writing of her Book, she finally saw-—while reading out her putrid, mewling, nagging complaint against the gods—-how Truth rewrites all we ever thought we knew, shows us our very “virtues” to be the shabby, tarnished, raggedy things they are—and were, if we could have but seen it.

And the ending is the most Sublime piece of writing I have encountered. This, from a lover of Dante, Wordsworth, The Winter’s Tale, whatever glorious and lofty poems you have to offer. That beauty, however, does not reside (primarily or exclusively) in the words themselves. Yes, Lewis knows exactly what word to use in every case. But he intentionally chose an idiomatic style, an almost blue-collar diction, as it were. Now, in TWHF, that language rises to suit its subject, but it’s still not Virgilian. No, the sublimity comes through the words. And for me it resides here:

“I know now, Lord, why you utter no answer. You are yourself the answer. Before your face questions die away. What other answer would suffice?”

And there is a perfect summary of Christian theology; all you need to know to be saved, yet couched in a pagan story. That is sanctified genius, I believe.

Mom, does that help??

Listened to: Vivaldi’s “Autumn,” favorite Bollywood songs, the soundtrack to “Apollo XIII.”

Watched: The Question of God: Sigmund Freud & C. S. Lewis debate God, love, sex, and the meaning of life and World Trade Center.

"Psyche" by Leighton

I said in my last post, “There are two main beauties of Till We Have Faces. One is the ‘big idea,’ Lewis’s mythopoeia,” and of this I intend to speak now. I called it previously “Christian Mythology,” and located it in Part II of this great book. What could I possibly mean by “Christian Mythology?” That sounds offensive to the Truth. But let me try to explain what CSL meant by it.

In Surprised by Joy, he writes that he had been taught, as a child, that Christianity was 100% true, and all other religions were 100% false. When he came to love the poetic beauty of the Norse myths (“Balder the beautiful is dead, is dead!”), he felt his soul moved in a way that none of his early Christian teaching had moved him. Also, during his theistic days, he felt his mind moving towards Christianity, but couldn’t understand the essence of it. Sinfulness, the need for redemption, that he got quite clearly. But he couldn’t, as he put it in a letter to Arthur Greeves, see how the life and death and resurrection of a man 2000 years ago had anything to do with spiritually rescuing people nowadays. Tolkien and Barfield came over to talk some sense—or supra-sense—into him. They reminded him that when he came across the idea of substitutionary sacrifice in a pagan myth, he was not only not offended by it, he loved it and was strangely moved, profoundly affected by something mysteriously and deeply true about it in a way that could not be translated into simple prose. The death and resurrection of, say, Gilgamesh, was beautiful and powerful in its mythological setting. Well, then, said Tolkien, Christ’s death and resurrection works the same way. It’s a sacrifice with all the emotional and psychological power of a myth, but with this enormous difference: it actually happened. The others didn’t happen in history, but they were God’s way of preparing the human soul and imagination to accept it when it did really happen. In other words, God put the concept of sacrifice deep into our spirits so that even pagan writers who do not believe in it feel its power and work it into their greatest poems/plays/etc.

This conversation with Tolkien & Barfield was enormously important to Lewis. A few days later (on 28 September 1931, to be exact) he came to believe that Jesus is indeed the Son of God. He finally knew how sacrifice works, and he knew it somewhere even deeper than in his intellect, in some place in his soul that didn't have to turn in into a mathimatical proof. In short, he was converted/justified/redeemed.

From then on, CSL e felt that the idea of Christianity as the "true myth" solved the terrible problem of comparative religions—it answered that awful question, “How can your religion be perfectly true and all others perfectly false when they have important bits in common?” It explained to him, in a huge and universal way, the principles of Natural Law (otherwise known as General Revelation) outlined in Romans chapter one. It set him at rest, that he could fully commit his intellect to Christianity and it would actually help him understand the cultural and literary significance of all the other religions and philosophies that stirred his poetic imagination and thrilled his heart.

So he created a perfect myth. Till We Have Faces is one of his last books and, I believe, his best. The very feeling and faith of the pagan religion of Glome is inherent to TWHF. The Cult of Ungit is at once a false religion (“It’s very strange that our fathers should first think it worth telling us that rain falls out of the sky, and then, for fear such a notable secret should get out… wrap it up in a filthy tale so that no one could understand the telling”) and yet reveals true spiritual principles. The poor woman who come with her offering finds calm and peace and comfort in praying to that shapeless mass of stone. The crowds greeting the priest are full of joy. Every poor man and woman in that pitiful kingdom longs for the divine, longs for the comfort and the beauty of the gods.

And Orual rejected it. She became Ungit; ugly in soul, unmendable. She came to “the very bottom”; her nakedness before the gods, the worst and best that could be true. This is the first necessary stage of conversion: abject remorse, bitter horror at one’s own worthlessness, the depth of one’s own sin. At the river, the god told her “Die before you die; there is no chance after.” She needed to be buried in baptism and rise again out of herself. She had turned away from Joy, from “the everlasting calling, calling, calling of the gods.”

But in the very writing of her Book, she finally saw-—while reading out her putrid, mewling, nagging complaint against the gods—-how Truth rewrites all we ever thought we knew, shows us our very “virtues” to be the shabby, tarnished, raggedy things they are—and were, if we could have but seen it.

And the ending is the most Sublime piece of writing I have encountered. This, from a lover of Dante, Wordsworth, The Winter’s Tale, whatever glorious and lofty poems you have to offer. That beauty, however, does not reside (primarily or exclusively) in the words themselves. Yes, Lewis knows exactly what word to use in every case. But he intentionally chose an idiomatic style, an almost blue-collar diction, as it were. Now, in TWHF, that language rises to suit its subject, but it’s still not Virgilian. No, the sublimity comes through the words. And for me it resides here:

“I know now, Lord, why you utter no answer. You are yourself the answer. Before your face questions die away. What other answer would suffice?”

And there is a perfect summary of Christian theology; all you need to know to be saved, yet couched in a pagan story. That is sanctified genius, I believe.

Mom, does that help??

04 September 2006

An excuse for a short post: a great Chesterton quote

Sometimes I think I don't have time to do a proper post so I put it off for a long time. But I miss seeing regular activity on the blog, and a short sweet post is better than none at all.

I recently came across this great quote on Ron Reed's Soul Food Movies blog (his blog is a sneak preview of what'll be in his book, Soul Food Movies: A Guide to Films with a Spiritual Flavour).

"I don't deny that there should be priests to remind men that they will one day die. I only say it is necessary to have another kind of priests, called poets, actually to remind men that they are not dead yet." G.K. Chesterton

Well, I'm not dead yet. I've been meaning to do a post on Christianity and film, and haven't gotten around to it yet, but I figure pointing you towards Ron's blog is at least a step in the right direction.

I recently came across this great quote on Ron Reed's Soul Food Movies blog (his blog is a sneak preview of what'll be in his book, Soul Food Movies: A Guide to Films with a Spiritual Flavour).

"I don't deny that there should be priests to remind men that they will one day die. I only say it is necessary to have another kind of priests, called poets, actually to remind men that they are not dead yet." G.K. Chesterton

Well, I'm not dead yet. I've been meaning to do a post on Christianity and film, and haven't gotten around to it yet, but I figure pointing you towards Ron's blog is at least a step in the right direction.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)