Listened to: Vivaldi’s “Autumn,” favorite Bollywood songs, the soundtrack to “Apollo XIII.”

Watched: The Question of God: Sigmund Freud & C. S. Lewis debate God, love, sex, and the meaning of life and World Trade Center.

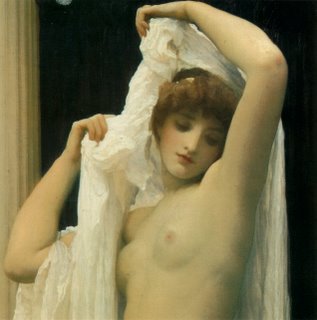

"Psyche" by Leighton

I said in my last post, “There are two main beauties of Till We Have Faces. One is the ‘big idea,’ Lewis’s mythopoeia,” and of this I intend to speak now. I called it previously “Christian Mythology,” and located it in Part II of this great book. What could I possibly mean by “Christian Mythology?” That sounds offensive to the Truth. But let me try to explain what CSL meant by it.

In Surprised by Joy, he writes that he had been taught, as a child, that Christianity was 100% true, and all other religions were 100% false. When he came to love the poetic beauty of the Norse myths (“Balder the beautiful is dead, is dead!”), he felt his soul moved in a way that none of his early Christian teaching had moved him. Also, during his theistic days, he felt his mind moving towards Christianity, but couldn’t understand the essence of it. Sinfulness, the need for redemption, that he got quite clearly. But he couldn’t, as he put it in a letter to Arthur Greeves, see how the life and death and resurrection of a man 2000 years ago had anything to do with spiritually rescuing people nowadays. Tolkien and Barfield came over to talk some sense—or supra-sense—into him. They reminded him that when he came across the idea of substitutionary sacrifice in a pagan myth, he was not only not offended by it, he loved it and was strangely moved, profoundly affected by something mysteriously and deeply true about it in a way that could not be translated into simple prose. The death and resurrection of, say, Gilgamesh, was beautiful and powerful in its mythological setting. Well, then, said Tolkien, Christ’s death and resurrection works the same way. It’s a sacrifice with all the emotional and psychological power of a myth, but with this enormous difference: it actually happened. The others didn’t happen in history, but they were God’s way of preparing the human soul and imagination to accept it when it did really happen. In other words, God put the concept of sacrifice deep into our spirits so that even pagan writers who do not believe in it feel its power and work it into their greatest poems/plays/etc.

This conversation with Tolkien & Barfield was enormously important to Lewis. A few days later (on 28 September 1931, to be exact) he came to believe that Jesus is indeed the Son of God. He finally knew how sacrifice works, and he knew it somewhere even deeper than in his intellect, in some place in his soul that didn't have to turn in into a mathimatical proof. In short, he was converted/justified/redeemed.

From then on, CSL e felt that the idea of Christianity as the "true myth" solved the terrible problem of comparative religions—it answered that awful question, “How can your religion be perfectly true and all others perfectly false when they have important bits in common?” It explained to him, in a huge and universal way, the principles of Natural Law (otherwise known as General Revelation) outlined in Romans chapter one. It set him at rest, that he could fully commit his intellect to Christianity and it would actually help him understand the cultural and literary significance of all the other religions and philosophies that stirred his poetic imagination and thrilled his heart.

So he created a perfect myth. Till We Have Faces is one of his last books and, I believe, his best. The very feeling and faith of the pagan religion of Glome is inherent to TWHF. The Cult of Ungit is at once a false religion (“It’s very strange that our fathers should first think it worth telling us that rain falls out of the sky, and then, for fear such a notable secret should get out… wrap it up in a filthy tale so that no one could understand the telling”) and yet reveals true spiritual principles. The poor woman who come with her offering finds calm and peace and comfort in praying to that shapeless mass of stone. The crowds greeting the priest are full of joy. Every poor man and woman in that pitiful kingdom longs for the divine, longs for the comfort and the beauty of the gods.

And Orual rejected it. She became Ungit; ugly in soul, unmendable. She came to “the very bottom”; her nakedness before the gods, the worst and best that could be true. This is the first necessary stage of conversion: abject remorse, bitter horror at one’s own worthlessness, the depth of one’s own sin. At the river, the god told her “Die before you die; there is no chance after.” She needed to be buried in baptism and rise again out of herself. She had turned away from Joy, from “the everlasting calling, calling, calling of the gods.”

But in the very writing of her Book, she finally saw-—while reading out her putrid, mewling, nagging complaint against the gods—-how Truth rewrites all we ever thought we knew, shows us our very “virtues” to be the shabby, tarnished, raggedy things they are—and were, if we could have but seen it.

And the ending is the most Sublime piece of writing I have encountered. This, from a lover of Dante, Wordsworth, The Winter’s Tale, whatever glorious and lofty poems you have to offer. That beauty, however, does not reside (primarily or exclusively) in the words themselves. Yes, Lewis knows exactly what word to use in every case. But he intentionally chose an idiomatic style, an almost blue-collar diction, as it were. Now, in TWHF, that language rises to suit its subject, but it’s still not Virgilian. No, the sublimity comes through the words. And for me it resides here:

“I know now, Lord, why you utter no answer. You are yourself the answer. Before your face questions die away. What other answer would suffice?”

And there is a perfect summary of Christian theology; all you need to know to be saved, yet couched in a pagan story. That is sanctified genius, I believe.

Mom, does that help??

3 comments:

"Tolkien and Barfield came over to talk some sense—or supra-sense—into him."

Well put. I think this lynchpin in Lewis's conversion often gets overlooked...the fact that he saw "true myth" as a category more mysterious and worship-inspiring than any mere "theory" or "system" of theology. Lewis wanted the truth, yes, but he didn't want it dry and categorical. He was looking for divine revelation in all its richness, a richness he had already sensed...

I too love the closing lines of TWHF. Reading your post, I'm thinking it's about time I read it again.

I think it's almost always time to read it again! :)

Read: Moby Dick (finally finished; worth getting all the way through!)

Listened to: The Beatles 1962-1966 and The Beatles 1967-1970.

Another idea of Tolkien's, which I think may have influenced Lewis in his conversion, was what Tolkien termed the eucatastrophe ("good catastrophe") of a story, i.e., the "consolation" or "Happy Ending" or "sudden joyous turn." According to Tolkien, the Gospels contain "the greatest and most complete conceivable eucatastrophe....The Birth of Christ is the eucatastrophe of Man's history. The Resurrection is the eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation." (Tolkien, "On Fairy Stories" in The Tolkien Reader, Ballantine, 1966, pp. 88-89).

In looking for documentary evidence of Tolkien's "eucatastrophe" influence on Lewis, I stumbled upon a very interesting master's thesis: A Celebration of Joy: Christian Romanticism in the Chronicles of Narnia (Michael Dean Bellah, West Texas A&M University, 1995). In his chapter on "eucatastrophe," while he didn't answer my question about whether Lewis's conversion was partly aided by the idea of Christ as the Great Eucatastrophe, he does point out the motif's literary influence on Lewis: each of the Chronicles of Narnia ends in eucatastrophe. I can't remember TWHF enough to know whether it ends in a eucatastrophe too, but I wouldn't be surprised.

Also, a couple of good blog posts on myth in Lewis, Tolkien, and Christianity that I found while researching this: Finding True Myth (Michael Russell, "Lord of the Kingdom" blog) and Mommy, What's a Myth? ("Wonders for Oyarsa" blog)

Post a Comment