Lewis’ Neo-Platonism

By Judith Eurydice

The Greek philosopher Plato has influenced nearly every great thinker in history. Casting his writings in the form of dialogues between his mentor Socrates and Socrates’ disciples and friends, Plato presented his ideas in an engaging, logical setting. Some twenty-three hundred years after the philosopher’s death, C. S. Lewis absorbed and reworked some of his doctrines into advocates of the Christian faith. His writings are permeated with Platonic ideas, images, and reasoning. From the belief in absolute truth right up through the theory of the forms, this essay will trace the streams of thought that flowed from the philosopher’s writings into Lewis’ theology and fiction. We will discuss how these two great thinkers built on a foundation of absolutes and how they dealt with the dichotomy of appearance versus reality.

The dialogue Republic discusses at the length the question of absolutes. In it, Socrates sets out to describe an ideal state and the qualities its rulers must possess. He challenges his audience, especially Glaucon (Plato’s older brother) to explain justice so they can find a leader with this all-important quality. True to form (no pun intended), Plato is using this discussion as an opportunity of opening up a great many metaphysical and ethical questions: what is justice? why should we practice it? what is our standard for just behavior? All these questions center on the issue of absolute values. C. S. Lewis embraced Biblical absolutes for truth and morality in a time when faith in traditional Christianity had crumbled, post-modernism had brought relativism, and materialism was closing its grip on contemporary thought.

The philosophical question known as “the problem of evil” had long kept Lewis from the Christian faith: if God is good and all-powerful, how is there evil in the world? Ironically, the reverse side of this very problem helped to drive him to God. A scholar from the C. S. Lewis Institute has explained this flip side of the problem of evil succinctly:

“[I]f evil exists, there must be a fixed, absolute, transcendent standard by which we can know it to be evil. If there is real evil, then we must have a fixed standard of good by which we judge it to be evil. This absolute standard points toward God as a being who has this absolute standard in Himself.” (Lindsley 2)

The view of God as the absolute standard runs parallel to Plato’s standard of good: the Good, the highest of the “forms.” Before we will follow these parallels through Lewis’ writings, an explanation of these “forms” is in order.

The Republic is the first dialogue in the Platonic canon to discuss his famous theory of the “forms.” The Greek word, eidos, can also be rendered: idea, ideal, archetype, thing-in-itself, or true reality. In order to illustrate his idea of reality, Socrates asked Glaucon to consider an everyday object, such as a table or a bed. (596b) He then showed how a carpenter might make many different beds, but they all share that same essential quality of being a bed. Whatever that commonality is that makes an item of furniture a bed is the “form.” In order to produce an object that can properly be called a bed, the craftsman has in mind (whether or not he is conscious of it) the appropriate form. The carpenter produces “not the form of bed which according to us is what a bed really is, but a particular bed.” (597a) He concludes that the carpenter’s bed is not “ultimately real;” the only real bed-in-itself is the eidos of bed as created by God. An excellent description of the nature of eidē follows: “Forms cannot be the objects of fleeting sensation, but are the unchanging objects of adequate definition, arrived at through logos. They are variously spoken of as eternal, invariable, indestructible, and ungenerated. Their permanent existence would seem to be out of time and non-temporal, rather than enduring through time, since they are purely what is defined in knowledge.” (Schipper 4) Similarly, in other dialogues, Plato asked his friends to define justice; they could do no better than cite various examples of just acts being performed. Plato then brought them round to the “idea” or eidos of justice. Thus we have Plato’s belief in absolutes.

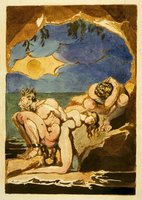

The illustration of the bed comes during a discussion of art: Plato believed that art was unnecessary and even harmful, because it is a representation of earthly things, which is in turn produced from the reality of the forms. Therefore, art is thrice removed from “reality.” (597e) p.425 “Suppose, then, that a man could produce both the original and the copy. Do you think he would seriously want to devote himself to the manufacture of copies and make it the highest object in life?” (599b) However, he goes on to suggest that poets like Homer would have been truer to reality if they had gone off and actually fought in battles rather than merely writing about them. Here, we can be thankful that Lewis parted ways with the old philosopher and continued making mere representations. Ironically, the whole structure of the dialogues is in a way deceptive, and far removed from reality: Plato put all these words into Socrates’ mouth and the character of Socrates often uses parables to illustrate his points. Therefore, the doctrines that come to us through these writings could be considered thrice-removed from reality. I would speculate though he dutifully recorded Socrates’ rejection of anything that was not real in the truest sense, Plato understood the value of parables and fables in communicating truths. Lewis certainly understood: chose to use whatever means he could to reach lost souls: he believed in the power of myths in pointing to heavenly truths.

The theory of the forms is presented in the Republic by means of three different “similes” of which we will discuss the most famous: the Simile of the Cave. Book seven describes prisoners in a cave—prisoners from childhood—chained in such a way that they can only look straight before them at the back wall of the cave. Behind them burns a fire and men are carrying objects between them and a fire, creating shadows on the back wall. The prisoners would assume that the shadows they saw were the real objects themselves, having known no other reality (515c). One prisoner, however, was forcibly freed and brought out of the cave into the sunlight. While his eyes were becoming adjusted to the light, they would be pained and dazzled. Once his eyes are able to handle the light, he realizes that what he believed in before were but shadows. He observes the world around him, and finally raises his eyes and recognizes the sun as the means by which he is able to perceive reality. Plato explains the analogy thus:

“The realm revealed by sight corresponds to the prison, and the light of the fire in the prison to the power of the sun. And you won’t go wrong if you connect the ascent into the upper world and the sight of the objects there with the upward progress of the mind into the intelligible region… the final thing to be perceived in the intelligible region… is the form of the good; once seen, it is inferred to be responsible for whatever is right and valuable in anything… being in the intelligible region itself controlling source of truth and intelligence.” (517b)

The simile of the cave best illustrates the disjuncture of appearance versus reality that permeates Lewis’ literature. Not just a philosophical speculation, this dichotomy should bring us to realize: this world that we see is not all there is. We should be led, as Lewis was, to seek out true reality. We as Christians know that truth will always point us to Jesus our Savior. Lewis, a professor of medieval literature, was very familiar with the neo-Platonism of the Middle Ages. Combining views of Plato and Aristotle with Christian principles had been in vogue among intellectuals of that era. As the sun illuminates the visible world, revealing images and sensible objects, so the Good enables us to perceive the intelligible world of the pure reason and the forms. Similarly, they pointed out that the Son illuminates our souls and God enables us to perceive spiritual truths. Revelation tells us that in heaven we will not need the sun: the glory of God is its light and the Lamb is its lamp. However, in this world, the process of spiritual/intellectual enlightenment is not any easy one. The light of the sun was too much for the prisoner’s eyes, and in The Great Divorce, “reality is harsh to the feet of shadows.” (42) But this struggle and pain is part of the process of apprehending the forms and becoming a real, solid person instead of a ghost.

The philosophic idea that is most represented in Lewis is that of “reality versus shadows.” The one who gets out of the cave and sees reality is not believed by the others when he returns to the cave with the good news. There are examples of this throughout Lewis, especially in the Narnia Chronicles: In Prince Caspian, Lucy’s siblings are at first unable to see Aslan, then they see only his shadow, and finally himself, rather like the prisoner emerging from the cave. The Witch of The Silver Chair nearly convinces the children and Puddleglum that their world is really only a dream. Lewis toys with the philosophy of the forms and their particulars: the Witch tells them their idea of a sun is only dream-copy of the lamp which hangs from her ceiling. She suggests that their image of Aslan is drawn from having seen a housecat and dreamed of one larger and better. Of course she is reversing the truth: Aslan is infinitely larger and better—He is the form from which the housecat was copied. The final two chapters of The Last Battle show Lewis at his most Platonic. Perhaps the saddest scene in the whole book is the scene in with the dwarves in “heaven.” True materialists, they refused to be “taken in” by the glorious new experience. They were stuck in their pathetic, self-made reality. But their Narnia “was not the real Narnia. That had a beginning and an end. It was only a shadow or a copy of the real Narnia… just as our own world, England and all, is only a shadow or copy of something in Aslan’s real world.” (169) In fact, the final chapter of the Narnia Chronicles is entitled “Farewell to Shadowlands.”

For those of us how sense in our souls that our world is not truly real, there is a deep yearning to find fulfillment. That is the reason, Lewis explains, that “we have peopled air and earth and water… with gods and goddesses.” (Weight of Glory 16) We cannot fully participate in Nature, but we feel that we are somehow meant to do so; therefore we invent deities to inhabit and enjoy Nature from the inside for us. But the promise of Christianity is that “…we shall get in… that greater glory of which Nature is only the first sketch” (Weight of Glory 17) Here we are invited to “participate” in the forms. This is why Lewis can say in The Great Divorce “…any man who reaches Heaven will find that what he abandoned… was precisely nothing: that the kernel of what he was really seeking even in his most depraved wishes will be there, beyond expectation, waiting for him in the ‘the high Countries.’” (6)

A little-known essay, “Transposition,” contains some of Lewis’ best work in this vein. It is an argument against materialism—the belief that what we see is all there is. The skeptic thinks that spiritual ideas are derived from natural ones (61). He dismisses religious beliefs and spiritual experiences by scientifically explaining them away. To borrow the key phrase from Lewis’ Miracles, the skeptic considers this world of our five senses is “the whole show.” Lewis contends that spiritual truths are so much greater than our experience here, that they must be scaled down to something we can understand: they must be “transposed” from a richer to a poorer medium (60) True to the spirit of Plato, Lewis illustrates his point with a “parable”: the parable of the artist’s son. (68) An artist was in prison and gave birth to her child there. He was raised knowing nothing of the outside world (does this sound familiar?). She drew him pictures of what the world was like outside of the prison, but when she tried to describe how it really looked different from her sketches, he asked, “What no pencil marks there?” Our senses can not apprehend the reality of the spiritual realm: we cannot see it only because it is “incomparably more visible.” (69)

That Hideous Strength contains an unnerving parody on this whole idea of reality. The character of Mark Studdock has too much materialistic education and too little human interaction, as well as no faith or belief: “his education had had the curious effect of making things that he read and wrote more real to him than the things he saw. Statistics about agricultural labourers were the substance; any real ditcher, ploughman, or farmer’s boy was the shadow.” He has a serious personal spiritual problem: a lack of concern for people as individuals, as creations in the image of God. This is further shown through his “…great reluctance, in his work, ever to use such words as ‘man’ or ‘woman.’ He preferred to write about ‘vocational groups,’ ‘elements,’ ‘classes,’ and ‘populations’…” What is fascinating about this description is Lewis’ wry, ironic comment: “he believed as firmly as any mystic in the superior reality of the things that are not seen.” (93) This is Hebrews 11 material with Platonic overtones; Lewis has deliberately twisted the perspective, setting the mood of bitter skepticism. This passage reminds us of Plato’s rejection of art: Mark is trebly removed from “reality.” He has sunken to contemplating shadowy descriptions of people who are in turn themselves only “shadows.”

The problem with materialism is that it treats this poor land of shadows like reality. Plato would recognize in the Hell of The Great Divorce our own world. This wonderful book has all of Hell fit into a small crack in the ground of Heaven. When a ghost tried to pocket an apple (a “real commodity”) to take back with him, an angel told him, “Put it down; there is not room for it in Hell.” (52) The painter was unable to appreciate the reality of the heavenly landscape. He had loved paint only as a means for portraying the light that he loved. Then he had gradually come to love paint “for its own sake.” (81) One of the Solid People tried to remind him: “When you painted on earth… it was because you caught glimpses of Heaven in the earthly landscape. The success of your painting was that you allowed others to see the glimpses too. But here you have the thing itself.” (80) It does not get much more Platonic than that! Excepting, perhaps, the statement, also in The Great Divorce, “Heaven is reality itself. All that is fully real is heavenly.” (69)

Plato would have endeavored to free the soul through intellectual disciplines. The soul, the mind, intellect—these are the part of man that can apprehend the eide. He hoped to purify the soul by freeing it from bodily interference. That is because he believed the forms to be the only true facts, therefore, the only facts worth knowing. The Great Divorce refers to God as “Truth, the Eternal fact.” (44) This echoes the belief of Lewis’ friend Charles Williams (whose Place of the Lion has the Platonic Ideals break into our world and roam the English countryside wreaking havoc) that “the glory of God is in facts” (The Redeemed City) and “all facts are joyful” (Descent into Hell) because they are part of God’s unalterable will. Lewis emphasized denial of the Self; not necessarily the body’s physical needs or wants, but the Self that sets itself up as an individual as opposed to a mere reflection of its Creator. One can participate in the Form or not and thus be clothed in His glory or not. I wish Plato and Lewis could have met; Lewis is almost a philosophical Messiah, fulfilling and redeeming the prophecies of the ancients. What Plato and Lewis both endeavor to do is to force our spiritual gaze ever upward. We are created in the image of God. He is the form on which we are based. We are but shadows or copies of him. But we are invited to become more like Him; we are invited to participate in the Form who created the forms. He is our Eidos, our archetype, our thing-in-itself. In the words of the Professor: “It’s all in Plato, all in Plato: bless me, what do they teach at these schools!”

Lewis, C. S. The Chronicles of Narnia. Prince Caspian. The Silver Chair. The Last Battle.

New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1946.

Lewis, C. S. The Screwtape Letters. The Best of C. S. Lewis. New York: Christianity

Today, inc., 1969. 16, 17

Lewis, C. S. The Great Divorce. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1946. 80, 42, 44, 6

Lewis, C. S. That Hideous Strength. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1946.

Lewis, C. S. “The Weight of Glory” and “Transposition.” The Weight of Glory and Other

Addresses. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1962.

Lindsley, Dr. Art. “C. S. Lewis on Absolutes.” Knowing and Doing. C. S. Lewis Institute.

Fall 2002.

Plato. Republic. Desmond Lee, translator. Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1974.

Schipper, Edith Watson. Forms in Plato’s Later Dialogues. The Hague, Netherlands:

Martinus Nijoff, 1965.

Lecture notes from “Introduction to Philosophy” Spring 2003 and “Philosophy of Religion” Spring 2004 with Dr. Danaher

This is a photo I took in the Old Masters Gallery at the Zwinger Palace in Dresden. It demonstrates the three difference paces at which people take in an art museum (you can click on it to enlarge it to see this better). There are those who rush through trying to see as much as they can (the lady on the left going by so fast she's a blur). Others stand for a long time in front of each painting (the lady facing away from us who stood without budging for the entire long exposure). And some are so pooped out by the whole experience that they just sit around on the benches. Which is your art museum pace?

This is a photo I took in the Old Masters Gallery at the Zwinger Palace in Dresden. It demonstrates the three difference paces at which people take in an art museum (you can click on it to enlarge it to see this better). There are those who rush through trying to see as much as they can (the lady on the left going by so fast she's a blur). Others stand for a long time in front of each painting (the lady facing away from us who stood without budging for the entire long exposure). And some are so pooped out by the whole experience that they just sit around on the benches. Which is your art museum pace?